HyperRegionalism: Lecce between layers of history and futuristic visions

In October 2024, Lecce hosted the thirteenth edition of “Architects Meet”, an event conceived by AIAC (Italian Association of Architecture and Criticism), in collaboration with the Municipality of Lecce, the Polo Biblio-Museale and the Order of Architects PPC of Lecce. The theme chosen for this edition, “HyperRegionalism”, materiality and immateriality of Architecture”, explored a contemporary trend that contrasts global homogeneity with a rooted and recognizable architecture, capable of combining technological innovation and local tradition.

The concept of “HyperRegionalism” is based on a new balance between traditional and advanced technologies, with a particular focus on sustainability and energy efficiency. As underlined by the architectural critic and historian Luigi Prestinenza Puglisi, president of AIAC, the theme represents a response to standardization: “We recover significant fragments of pre-existing structures to create a dialogue between old materialities and new immaterial flows.”

underlined by the architectural critic and historian Luigi Prestinenza Puglisi, president of AIAC, the theme represents a response to standardization: “We recover significant fragments of pre-existing structures to create a dialogue between old materialities and new immaterial flows.”

The days of the event saw the involvement of architects, critics and designers from all over Italy and abroad, who shared projects emblematic of this vision.

Lecce, chosen for its unique architectural heritage, was the ideal setting for the event. The main venues, including the Teatro Paisiello, the Biblioteca Bernardini and the Church of Santa Maria di Ogni Bene, hosted conferences, exhibitions and meetings, creating an immersive experience for participants.

Manuel Aires Mateus, an internationally renowned Portuguese architect, received the International Award “Architects Meet in Lecce 2024”. During his lectio magistralis at the Teatro Paisiello, he illustrated the restoration project of Torre 67 in Alezio, an example of how the recovery of the past can coexist with sustainable contemporary design.

Manuel Aires Mateus, an internationally renowned Portuguese architect, received the International Award “Architects Meet in Lecce 2024”. During his lectio magistralis at the Teatro Paisiello, he illustrated the restoration project of Torre 67 in Alezio, an example of how the recovery of the past can coexist with sustainable contemporary design.

Along the dry stone walls of a narrow country lane in Southern Salento, you reach Torre67, Mateus’s first project in Puglia. The tower, with a square plan and structured on two levels, rises in the heart of the rural area of Alezio (Lecce). Immersed in a landscape of crops, vineyards and wild flowers, two olive trees marked by Xylella welcome the entrance, like columns that evoke the memory of a now lost landscape. Built between the 12th and 14th centuries, initially intended for sighting purposes, the tower has undergone several transformations over time, maintaining traces of religious symbolism. Today, thanks to the rigorous restoration work of the Portuguese studio, the tower returns to its original form.

The restoration, completed in 2024, was based on the enhancement of the historical value of the site, with the aim of returning the tower to its original structure. The intervention involved the elimination of additional bodies and highlighted the tuff walls and the original openings. A radical approach, given that the tower is not constrained and that part of the demolished structures have not been rebuilt, but reused to create new components: the swimming pool, with a shape that replicates the tower, and the paths in the surrounding landscape.

The building was transformed into a residence for two clients from Milan who chose to live in Puglia. The living area is on the ground floor, while on the first floor there is a bedroom, a bathroom and a small office. All the rooms are characterised by traditional vaults and floors in cocciopesto, beaten tuff and travertine, while the walls are finished with lime and hemp. The choice to fully preserve the structure, the use of local and natural materials for the furnishings and the absence of air conditioning and heating systems are the most radical aspects of the project. The thermal inertia of the walls and natural ventilation partially compensate for the lack of cooling and heating systems.

The building was transformed into a residence for two clients from Milan who chose to live in Puglia. The living area is on the ground floor, while on the first floor there is a bedroom, a bathroom and a small office. All the rooms are characterised by traditional vaults and floors in cocciopesto, beaten tuff and travertine, while the walls are finished with lime and hemp. The choice to fully preserve the structure, the use of local and natural materials for the furnishings and the absence of air conditioning and heating systems are the most radical aspects of the project. The thermal inertia of the walls and natural ventilation partially compensate for the lack of cooling and heating systems.

This transformation represents an example of slow, almost monastic living, which distances itself from the frenetic pace of modern life and rediscovers values of the past, not only aesthetic but also linked to direct contact with the territory.

The project is part of a particularly current context in Puglia, where many historic buildings are being restored and transformed into homes or accommodation facilities, also thanks to the support of regional funds. In this region, the design rooted in the territory, which preserves historical memory, contrasts with the growing demand for comfort and high energy performance, a theme that was the subject of discussion during "Architects Meet” in Lecce.

The event was enriched by two exhibitions curated down to the smallest details:

- “HyperRegionalism”, curated by Riat Archidecor, presented over 100 projects by Italian studios, enhancing the relationship between historical pre-existences and innovative architectural solutions. The installation

- “HyperRegionalism”, curated by Riat Archidecor, presented over 100 projects by Italian studios, enhancing the relationship between historical pre-existences and innovative architectural solutions. The installation

was composed of wooden tables, then handcrafted with an ecological decorative paint in different shades of color, supported by some very essential iron elements. The tables hosted about 140 notebooks, each of which illustrated a project created by an architectural studio. The theme of the exhibition is Hyperregionalism: to an architecture without a soul, the same in all places, today we try to contrast spaces that are rooted and recognizable and constructions in which the material plays a leading role.

- “Supermostra 24”, curated by Ilaria Olivieri and Luigi Prestinenza Puglisi, an observatory and a traveling exhibition explored the work of 33 emerging designers, with the aim of verifying how much interest is happening in the field of architecture in the different regional areas of the peninsula, inaugurating the “STELO” exhibition system, an innovative project of the Polo Biblio-Museale of Lecce.

With over 600 registered attendees, “Architects Meet 2024” ended with an extremely positive balance. “We have laid the foundations for a profound reflection on the future of Italian architecture,” said Prestinenza Puglisi. The event transformed Lecce into an international capital of architecture, consolidating its role as a point of reference for contemporary architecture and for the dialogue between tradition and innovation.

The theme of HyperRegionalism, which explores an architecture in harmony with the local context, focused on the specificities of Salento, such as the use of Lecce stone and carparo. These materials were valorized as examples of sustainability and architectural innovation.

With an international participation of over 300 professionals and scholars, the event strengthened the visibility of Lecce and Salento, positioning them as a cultural and tourist center for architecture.

The event confirmed Lecce as a laboratory of architectural innovation, combining historical memory and contemporaneity. These annual meetings, if continued, will further consolidate the identity of Salento as a model of sustainable development based on the valorization of its unique resources.

Salt and Identity: the white thread that connects past and present

Salt, a substance that has accompanied humanity since the beginning, is more than just a seasoning: it is a universal symbol, a link between tradition, history, and culture. Always essential in daily life and sacred rituals, salt has profoundly influenced the evolution of civilizations, assuming both practical and spiritual meanings.

An ancient and valuable resource

Since ancient times, salt has been considered a valuable commodity. In ancient cultures, such as the Roman one, it was so important that it was used as a form of currency. The term "salary" actually derives from the practice of paying Roman soldiers with salt, a resource essential for food preservation and survival.

The Via Salaria, one of the oldest Roman roads, attests to the centrality of salt in the Empire's trade routes. This element, with its ability to preserve food, also symbolized incorruptibility and eternity. Its spiritual connotations are found in many cultures: in Christian rituals, it represents purity and covenant, while among Eastern peoples, the "salt pact" symbolizes a lasting and sacred agreement.

Salt in popular culture

Language and popular traditions reflect the importance of salt in everyday life. Expressions like "avere sale in zucca" (to have salt in the head) or "un conto salato" (a steep bill) evoke intelligence and value. In fairy tales and folk stories, salt becomes a recurring symbol. In Salento, for example, there is the story of the fisherman and the little fish named Salt, who, with cunning, proves to have more "salt in his head" than his captor.

The very name of Salento could also be linked to salt. According to a legend, the term comes from King Sale, a mythical ruler of the Messapi, an ancient people who inhabited these lands before the arrival of the Greeks and Romans.

Salt production: between ingenuity and resistance

Throughout history, salt production has often been regulated by the State. In Italy, the salt monopoly marked entire eras, leading to the persecution of those who tried to produce it illegally. The coasts of Salento, with their cliffs and natural cavities, were the site of ingenious but illegal production. Even today, along the coastal road between Gallipoli and Santa Caterina, traces of these improvised salt pans can still be seen, symbols of a daily struggle for survival.

The Salt Routes: between nature and history

One of the most fascinating examples of the connection between salt and the land is represented by the Salt Routes in Salento. Located near Corsano, these ancient roads, bordered by dry stone walls, once connected the salt collection ponds on the coast with the inland towns. Today, these paths represent a heritage of extraordinary natural and historical beauty.

Along the main paths, such as Nsepe, Scalapreola, and Scalamunte, visitors can immerse themselves in an untouched landscape, between the Mediterranean scrub and the crystal-clear sea. Walking on these ancient routes means traveling back in time, rediscovering the traces of a past that has shaped the identity of the land.

The Salina dei Monaci of Torre Colimena

Another extraordinary example of the connection between salt and the landscape is the Salina dei Monaci of Torre Colimena, located on the Ionian coast. This place, now a protected nature reserve, is a unique ecosystem where history and nature coexist harmoniously.

The name "Monaci" comes from the Benedictine monks, who, starting from the year 1000, transformed this area into a salt factory. Seawater would deposit during storms in a natural depression beyond the dunes, providing a reserve of what was once considered white gold, salt. To improve its exploitation, the monks carved the rock to create a channel for regulating the flow of water, and they built structures for processing and storing the salt, along with a watchtower and a frescoed chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Between the late 1800s and the 1940s, land reclamation efforts were proposed to address the malaria problem, which was particularly widespread here. Fortunately, the interventions were minimal and did not compromise the salt pans and their landscapes.

Starting in the 1960s, the salt pans were subject to heavy real estate speculation and uncontrolled tourist development. Dunes and large areas of Mediterranean scrub were destroyed, the groundwater was contaminated, and the salt pans were even used as a summer football field. In addition, the harmful presence of poachers exacerbated the situation.

Starting in the 1960s, the salt pans were subject to heavy real estate speculation and uncontrolled tourist development. Dunes and large areas of Mediterranean scrub were destroyed, the groundwater was contaminated, and the salt pans were even used as a summer football field. In addition, the harmful presence of poachers exacerbated the situation.

The following years marked a turning point, with a new environmental awareness and the commitment of institutions leading to protective interventions in the area and the establishment, in 2000, of the Torre Colimena Salt Pans Protected Area, which was included in the list of Italian protected areas in 2010.

The warehouses form a complex with barrel vaults and three rather spacious rooms (measuring 25×8 meters). The chapel is located a few dozen meters from the warehouse complex and still retains its original vault, with frescoed walls. The tower has a square base and a truncated pyramid shape.

Today, the reserve is an ideal habitat for rare species, such as the pink flamingos, and is surrounded by a lush Mediterranean scrub. The adjacent beach, with its golden dunes, adds to the charm of this destination, perfect for those seeking beauty and tranquility.

A heritage to preserve

Salt, with its millennia-old history, continues to be a valuable resource, symbolizing tradition, culture, and a connection to nature. The traces left by its use and production, such as the Salt Routes and the salt pans, represent an invaluable heritage that deserves to be cherished and protected.

Tourism and Infrastructure Development in Salento 2024: Deseasonalization and the Benefits for the Real Estate Sector

The Salento, a region in southern Apulia known for its crystal-clear sea, golden beaches, and remarkable local culture, continues to see steady growth in the tourism sector. In 2024, off-season tourism policies and investments in infrastructure have created new opportunities to extend the tourist season beyond the traditional summer months. This transformation not only brings economic benefits but also has a positive impact on the real estate market, creating new investment opportunities. Let’s take a closer look at tourism data, off-season initiatives, major non-summer events, benefits for the real estate sector, and ongoing infrastructure projects.

Tourism Data in Salento in 2024

In 2024, tourism in Salento reached new records, with a 15% increase in arrivals compared to the previous year. Growth is evident not only in peak summer months (June, July, and August) but also in shoulder periods like April, May, September, and October. This achievement was made possible by a strategy focused on showcasing the region even in less hot months, leveraging cultural, culinary, and natural aspects that attract a target of tourists interested in an authentic and diverse experience.

Visitor Origin and Profile

Most visitors come from Italy, but Salento also attracts foreign tourists, particularly from Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Visitors are typically between 25 and 50 years old, looking for a blend of relaxation, culture, and outdoor activities. New air connections and an increasing availability of services even outside the peak season have helped boost the region's appeal.

Tourism De-seasonalization: A Strategic Shift

De-seasonalization is a key strategy to make Salento a year-round destination. This policy enables the distribution of tourist flows over a longer period, easing pressure on the summer months and creating new income opportunities for local businesses. De-seasonalization not only enriches the tourism offering but also improves the quality of life for residents by creating stable jobs and supporting the local economy.

Off-Season Events in Salento

To encourage de-seasonalization, several events have been organized to attract visitors in autumn and spring:

- San Martino Festival (November): A popular event celebrating new wine paired with typical Salento gastronomic products, with village fairs and festivities.

- European Film Festival of Lecce (April or November): An event that draws film enthusiasts and professionals from across Europe, featuring screenings, workshops, and artist encounters.

- Salento Coast to Coast (May): A bike touring event through the villages of Salento's inland areas, offering a slow and sustainable tourism experience.

- Corti a Sud (October): A short film festival held in the historic villages of the region, involving young talent and cinema enthusiasts.

- Autumn and Spring Markets and Food Festivals: Culinary events in inland villages that promote local products like extra virgin olive oil, cheese, and cured meats.

Benefits of De-seasonalization for the Real Estate Sector

Tourism de-seasonalization has had a positive impact on the Salento real estate market, making the area attractive for both national and international investors. Here are the main benefits:

- Increase in Demand for Vacation Rentals and Short-Term Lets: With year-round tourism, the demand for vacation rentals has grown, not only in summer but also in spring and autumn. Property owners can thus rent their properties for longer periods and earn a steady income instead of relying solely on the summer season.

- Growth in Property Value: Properties in tourist locations or near historic villages are seeing increased value, as demand is driven by both tourism and the arrival of new residents. Moreover, improved infrastructure, such as new rail connections, enhances the value of properties near stations or major roads.

- Opportunities for Restoration of Historic and Rural Properties: De-seasonalization is encouraging the restoration of ancient farmhouses, "masserie," and "trulli," transforming them into accommodation options that cater to tourists seeking authenticity. Investors are rediscovering Salento's real estate heritage, converting historic buildings into B&Bs, agritourisms, and luxury vacation homes.

- Extension of the Rental Season: The ability to attract visitors year-round allows property owners to maintain high occupancy rates even outside peak season, boosting profitability.

New Infrastructure: Improved Railway Connections and Road Networks

To support tourism and enhance mobility, Salento is undergoing significant infrastructure projects, including the rail connection between Brindisi Airport and Lecce Station and the completion of the State Road 275.

Brindisi Airport – Lecce Railway Connection

One of the main obstacles for tourists choosing Salento is the lack of a direct connection between Brindisi Airport and Lecce, the gateway to the Salento peninsula. The new rail link project aims to address this gap, with shuttle trains connecting domestic and international flights arriving in Brindisi to the city of Lecce in under 30 minutes.

This connection will reduce the use of private cars, improving accessibility in Salento and promoting sustainable tourism. For international travelers, the convenience of a direct connection will make it easier to reach Salento, enhancing the region’s appeal to visitors from around the world.

Completion of the State Road 275

The State Road 275, also known as the “Maglie-Leuca,” is another key infrastructure to improve Salento’s road network. This long-awaited project involves the expansion and redevelopment of the road, which connects numerous towns and facilitates access to Capo di Leuca.

The realization of the State Road 275 will not only reduce travel times and traffic congestion but also allow for the distribution of tourist flows across the territory, improving accessibility to more remote locations. Additionally, this infrastructure represents a step forward for road safety, providing a more modern and secure communication route.

Conclusion

Thanks to de-seasonalization policies, off-season event organization, and infrastructure investments, Salento is establishing itself as a quality tourist destination capable of attracting visitors year-round. The growth in tourism and new opportunities in the real estate market signal a positive and sustainable development for the region.

The real estate sector directly benefits from this change, with an increase in demand for vacation homes and residential properties, growth in property values, and new investment opportunities in the restoration of historic buildings.

The Lecce Paper Mache: Art, Tradition, and Charm of Salento

The Lecce papier-mâché represents one of the most unique and fascinating artistic traditions of Salento. This ancient and lightweight art form arose from the need to decorate churches and sacred spaces without resorting to costly materials like marble or bronze. It was here that Lecce artisans, with their ingenuity and creativity, transformed paper into expressive sacred sculptures that became symbolic elements of the region

The Origins of Lecce Papier-Mâché

The art of papier-mâché dates back to the 17th and 18th centuries. The need to create sacred, evocative environments in churches without high costs inspired local artisans’ creativity. These papier-mâché pioneers used humble materials like paper, straw, cloth, and plaster, crafting sculptures capable of conveying extraordinary spirituality.

The art of papier-mâché dates back to the 17th and 18th centuries. The need to create sacred, evocative environments in churches without high costs inspired local artisans’ creativity. These papier-mâché pioneers used humble materials like paper, straw, cloth, and plaster, crafting sculptures capable of conveying extraordinary spirituality.

Local barbers, who devoted their free time to crafting sacred statues in the back rooms of their shops, were among the first to embrace this art. One of the earliest known masters was Mesciu Pietru de li Cristi, a barber renowned for making crucifixes, who in turn taught the craft to Mastr'Angelo Raffaele De Augustinis and Mesciu Luigi Guerra.

Over time, Lecce papier-mâché has been passed down through generations, enriched by techniques and secrets that still make this tradition unique. Lecce’s artisans have kept this art alive, allowing it to evolve while preserving its historical and symbolic value.

Techniques and Secrets of Papier-Mâché

Creating a papier-mâché statue is a meticulous process that begins with shaping the support structure, made by wrapping straw in twine to form the sculpture's core. Hands, feet, and the face are sculpted separately in terracotta and then attached to the main structure.

attached to the main structure.

At this stage, the statue is covered with layers of paper, glued with a special flour-based adhesive with water and a pinch of copper sulfate to protect against pests. Once dry, artisans use small, heated spoons in a process called "fuocheggiatura" to shape and solidify the structure, giving it expression and realism.

Next, the statue is coated with plaster—often Bologna plaster—to prepare the surface for final coloring. Oil colors are applied, and precise details bring every expression and fold of the drapery to life. Some artisans even make their own “earth tones” (from umber, Siena, and cinnabar) according to ancient methods known only to insiders.

Next, the statue is coated with plaster—often Bologna plaster—to prepare the surface for final coloring. Oil colors are applied, and precise details bring every expression and fold of the drapery to life. Some artisans even make their own “earth tones” (from umber, Siena, and cinnabar) according to ancient methods known only to insiders.

Its low cost and ease of production also made papier-mâché suitable for producing molds, copies, and affordable replicas. This accessibility, however, led to its long-standing classification as a “low-level” art form in the art hierarchy, often leaving it unpreserved despite its exceptional artistic potential.

However, this classification was challenged, notably by Vasari, one of the strongest proponents of the distinction between major and minor arts, who mentioned papier-mâché in his *Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects* (16th century). During the Renaissance, notable artists like Donatello experimented with the malleable, lightweight mixture, appreciating its expressive realism and softer form modulation, evoking deep introspection and spirituality.

After Donatello, nearly all renowned Florentine sculptors’ workshops dedicated themselves to replicating small and medium-sized papier-mâché reliefs. Popular subjects included Madonna and Child by Jacopo Sansovino, Desiderio da Settignano, Antonio Rossellino, and Benedetto da Maiano. The perfect blend of art and spirituality led to the large statues and decorations of Lecce’s Baroque style. Even today, the lightness of these statues allows them to be carried in the picturesque Holy Week processions, a major attraction in Puglia.

Papier-Mâché and Spirituality: The Papier-Mâché Museum

In Lecce’s historic center, the Papier-Mâché Museum celebrates this tradition with a collection of works representing centuries of history and devotion. Located in the Castello di Carlo V,

In Lecce’s historic center, the Papier-Mâché Museum celebrates this tradition with a collection of works representing centuries of history and devotion. Located in the Castello di Carlo V, near Piazza Sant'Oronzo, the museum hosts around 80 artworks, offering visitors a journey through the evolution of this ancient technique.

near Piazza Sant'Oronzo, the museum hosts around 80 artworks, offering visitors a journey through the evolution of this ancient technique.

Established in 2009, the museum has helped preserve and promote papier-mâché art, making it accessible to new generations and visitors from around the world. Walking through the museum's displays immerses visitors in Salento’s culture and history, unveiling the symbolic and religious significance of these sculptures.

Papier-Mâché Today: A Living and Renewing Art

Today, Lecce papier-mâché extends beyond sacred works, embracing a wide range of subjects and styles. Artisans continue to create nativity scenes, statues, and sacred reproductions, but their workshops also produce dolls, masks, interior decorations, and design objects. Papier-mâché has become a form of contemporary expression, capturing tradition while adapting to new aesthetics.

Today, Lecce papier-mâché extends beyond sacred works, embracing a wide range of subjects and styles. Artisans continue to create nativity scenes, statues, and sacred reproductions, but their workshops also produce dolls, masks, interior decorations, and design objects. Papier-mâché has become a form of contemporary expression, capturing tradition while adapting to new aesthetics.

During the Christmas season, Lecce celebrates its craft tradition with the "Antica Fiera dei Presepi e dei Pupi" (Old Fair of Nativity Scenes and Puppets), known as the Santa Lucia Fair. This event, akin to Naples' famous San Gregorio Armeno, takes place between Piazza Sant'Oronzo and Piazza Duomo, where visitors can purchase papier-mâché works created by local masters. The fair provides a unique opportunity to experience the beauty of papier-mâché and enjoy Salento's holiday atmosphere.

During the holidays, the former Teatini convent on Via Vittorio Emanuele also hosts an exhibition of artistic nativity scenes. Here, visitors can admire works by master papier-mâché artists and their students, offering a glimpse into the passion and dedication that still drives this ancient art today.

A Journey to Salento: Discovering Lecce Papier-Mâché

Lecce and Salento, with their traditions and history, make an ideal year-round destination, especially in winter when the city comes alive with cultural events and Christmas markets. Strolling through Lecce's historic center is a unique experience, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in a rare baroque setting among churches, palaces, and artisan workshops.

A trip to Salento during the Christmas season is a perfect opportunity to discover papier-mâché art, admire the works displayed at fairs and museums, and purchase unique souvenirs to take home. Lecce papier-mâché is a true cultural treasure that, thanks to the dedication of local artisans, continues to enchant generations of visitors.

Halloween and the Ancient Traditions of Salento

Halloween is a celebration that originates from Celtic traditions, yet some of its customs have taken root in Southern Italy during the long Norman domination. What connects Halloween to Salento? Although this occasion with its eerie atmosphere stems from ancient Celtic traditions, not everyone is aware that in Salento and Southern Italy, similar rituals exist, influenced by the Norman period and ancient Christian traditions intertwined with pagan rites.

For the Celts, the night of October 31 marked the end of the year and the moment when Samhain, the Lord of Death and Winter, gathered the souls of the deceased, who briefly reunited with the living. To prevent evil spirits from entering the bodies of the living, villagers would extinguish the fires in their homes, only to relight them at nightfall to burn offerings and perform protective spells. For three days, the Celts wore animal skins to ward off unwanted spirits, a practice that influenced the modern tradition of costumes.

Similarly, the ancestors of Salento and Southern Italy engaged in rituals honoring the deceased from October 31 to November 2. In some areas of Southern Italy, gifts and sweets are still prepared for children, with stories that they were left by deceased relatives; in other places, tables are set for a dinner believed to be attended by the souls of loved ones. In various locations, bonfires made from broom branches are lit in public squares, and leftovers from dinners are left outside for the deceased.

Similarly, the ancestors of Salento and Southern Italy engaged in rituals honoring the deceased from October 31 to November 2. In some areas of Southern Italy, gifts and sweets are still prepared for children, with stories that they were left by deceased relatives; in other places, tables are set for a dinner believed to be attended by the souls of loved ones. In various locations, bonfires made from broom branches are lit in public squares, and leftovers from dinners are left outside for the deceased.

The use of carved and illuminated pumpkins, a symbol of Halloween, also has Italian roots. But why is this tradition more closely associated with America today? The answer is simple: the United States is largely populated by descendants of Europeans, and the significant emigration from Southern Italy in past centuries carried many of these customs across the ocean.  Traditions such as "trick or treat" are linked to Southern Italy and likely gained traction in America as immigrants, finding themselves in a Protestant society, felt the need to keep their ancient Catholic and pagan traditions alive.

Traditions such as "trick or treat" are linked to Southern Italy and likely gained traction in America as immigrants, finding themselves in a Protestant society, felt the need to keep their ancient Catholic and pagan traditions alive.

Salento has a long-standing tradition of celebrations related to the dead that, in certain villages, bear a striking resemblance to Halloween rituals. In villages like Miggiano, Supersano, and Presicce, it was common to prepare banquets for the souls as a sign of hospitality. People would leave typical sweets, such as boiled wheat and "bones of the dead" cookies, outside their doors or on tables to welcome their deceased loved ones. Children were also given sweets as gifts.

Today, in some villages, like Zollino, the traditions for the Night of the Dead are still very much alive. Families prepare tables at home adorned with lit candles, food, and drinks to welcome the deceased. This practice not only honors the departed but also symbolizes the welcoming of their souls. During this time, a procession heads to the village cemetery, where candles are lit to illuminate the path for the souls.

In Martano, another vibrant tradition involves creating home altars in memory of the deceased, accompanied by moments of reflection and family meals featuring typical dishes such as boiled wheat and dried figs. The lights and decorative candles that adorn homes and streets evoke the modern illuminated pumpkins of Halloween.

In Specchia, one of the oldest and most picturesque villages in Salento, women still prepare pupurati, spiced cookies offered to children as a symbol of continuity between generations. In ancient times, bonfires were lit here to drive away evil spirits and protect the harvest, serving as a way to honor the deceased and maintain a connection to the spiritual world.

The Salento traditions related to the dead uniquely intertwine with the celebrations we now associate with Halloween. While Halloween has evolved differently elsewhere, in Salento, the celebrations on November 1st and 2nd continue to pass down rituals that connect the living with the deceased, in a night experienced as a moment of reflection, respect, and memory.

One of the most suitable places to host legends of witches and mysterious spirits in Salento is the area between Giuggianello, Giurdignano, and Minervino di Lecce, where ancient "natural monuments" endure, still living in collective memory. This territory, often compared to the famous Stonehenge for its dolmens, menhirs, and sacred stones, is rich in suggestive tales revolving around nymphs, old witches, and fairies known as "scazzamurieddhi." The local countryside, with its invaluable heritage, has inspired countless fantastic stories and fairy tales passed down through generations.

For instance, the Massi della Vecchia were the home of a witch called "la striara," who, at sunset, cast spells against those who dared to desecrate that sacred place. Anyone who dared to look her in the face was forced to jump endlessly, as an old nursery rhyme recounts: "Zzumpa pisara cu la camisa te notte…" ("Jump, witch, in your nightgown"), to which the victim responds, "se scappu de stu chiaccu nu nci essu chiui de notte" (if I escape this trouble, I won’t go out at night again).

For instance, the Massi della Vecchia were the home of a witch called "la striara," who, at sunset, cast spells against those who dared to desecrate that sacred place. Anyone who dared to look her in the face was forced to jump endlessly, as an old nursery rhyme recounts: "Zzumpa pisara cu la camisa te notte…" ("Jump, witch, in your nightgown"), to which the victim responds, "se scappu de stu chiaccu nu nci essu chiui de notte" (if I escape this trouble, I won’t go out at night again).

In another version of the legend, aided by an ogre or her husband, the witch would turn into stone anyone who could not answer her questions. Many fell into her trap, lured by the promise of a hen that laid golden eggs, resulting in the area being scattered with rocks.

In this same region, tales speak of a challenge between young people and fairies. Once, farmers forbade their children from going among the large stones, saying that the "fairies," beautiful but dangerous creatures, could appear there.

In Uggiano, stories of witches abound, who, during the sabbat, would gather around a "walnut tree by the windmill." It is said that a local innkeeper, on a full moon night, left her husband alone to join them. When the man noticed the food and wine running low, knowing his wife’s secret, he went to the meeting place but mispronounced the formula and was lifted upside down into the air. His wife saved him by reciting a spell that made him fall, but since then, that tree has remained "secret" to avoid misfortune. It is said to be located near an ancient underground oil mill, but no one has ever been able to pinpoint its exact location.

In Soleto, on the other hand, it is said that the Guglia degli Orsini del Balzo, a fascinating tower adorned with monstrous figures, was built in a single night by Matteo Tafuri, a renowned philosopher and esotericist. For the feat, he allegedly summoned witches and spirits, but at dawn, some of them, surprised by the rooster's crow, were petrified in the tower.

In Soleto, on the other hand, it is said that the Guglia degli Orsini del Balzo, a fascinating tower adorned with monstrous figures, was built in a single night by Matteo Tafuri, a renowned philosopher and esotericist. For the feat, he allegedly summoned witches and spirits, but at dawn, some of them, surprised by the rooster's crow, were petrified in the tower.

Few may know that in Tricase, the so-called Chiesa Nuova (or Church of the Devils) was said to be the work of the Devil, who erected it in a single night after making a pact with the so-called "Old Prince," traditionally identified as Messer Jacopo Francesco Arborio Gattinara, a real historical figure. According to legend, the events unfolded as follows: around the end of the 17th century, Messer Jacopo decided to support the numerous farmers working and living in the countryside (who wanted to drive away the Malobre, or evil spirits) by building a new church outside Tricase, on the way to the sea, which was historically completed in 1685, with an octagonal shape, dedicated to the Madonna of Constantinople. To this end—through the enchanted "Book of Command"—he thought to summon the Devil himself, with the secret intent of mocking him. The challenge proposed by the nobleman of Tricase was accepted by the Devil, on the condition that, within the same church, as an insult and mockery to God, the Old Prince would then offer the consecrated host to a goat, a symbol of Satan. For this commitment, in addition, the Lord of Darkness would leave a chest filled with gold coins in the Chiesa Nuova. Once the pact was sealed and the church erected, the morning after, the Devil reminded the Old Prince of his promise, which he denied ever having made. Feeling mocked, the Devil vented his rage by opening a water ditch near the church (known to the locals as the Canale del Rio) and throwing the church bells into it, which still seem to resonate with their deep tolls underground during stormy days. And what about the chest with the gold coins? The Old Prince had the opportunity to find and open it, but inside, it seemed, were insignificant coins made of base metal or even stones.

Prince," traditionally identified as Messer Jacopo Francesco Arborio Gattinara, a real historical figure. According to legend, the events unfolded as follows: around the end of the 17th century, Messer Jacopo decided to support the numerous farmers working and living in the countryside (who wanted to drive away the Malobre, or evil spirits) by building a new church outside Tricase, on the way to the sea, which was historically completed in 1685, with an octagonal shape, dedicated to the Madonna of Constantinople. To this end—through the enchanted "Book of Command"—he thought to summon the Devil himself, with the secret intent of mocking him. The challenge proposed by the nobleman of Tricase was accepted by the Devil, on the condition that, within the same church, as an insult and mockery to God, the Old Prince would then offer the consecrated host to a goat, a symbol of Satan. For this commitment, in addition, the Lord of Darkness would leave a chest filled with gold coins in the Chiesa Nuova. Once the pact was sealed and the church erected, the morning after, the Devil reminded the Old Prince of his promise, which he denied ever having made. Feeling mocked, the Devil vented his rage by opening a water ditch near the church (known to the locals as the Canale del Rio) and throwing the church bells into it, which still seem to resonate with their deep tolls underground during stormy days. And what about the chest with the gold coins? The Old Prince had the opportunity to find and open it, but inside, it seemed, were insignificant coins made of base metal or even stones.

Lastly, the Grotta delle Striare in Santa Cesarea Terme, located along the cliff between Porto di Castro and Porto Miggiano, is a cave with an eerie atmosphere. Legend has it that witches gathered there to dance and brew potions. Those who venture into the cave speak of pungent odors and rocks carved into the shape of female hands with elongated nails, resembling those of a witch, particularly highlighted at sunset with the sulfurous vapors appearing to emanate from enchanted cauldrons.

Lastly, the Grotta delle Striare in Santa Cesarea Terme, located along the cliff between Porto di Castro and Porto Miggiano, is a cave with an eerie atmosphere. Legend has it that witches gathered there to dance and brew potions. Those who venture into the cave speak of pungent odors and rocks carved into the shape of female hands with elongated nails, resembling those of a witch, particularly highlighted at sunset with the sulfurous vapors appearing to emanate from enchanted cauldrons.

Thus, while Halloween has Celtic roots, it finds a surprising affinity in the customs of Salento and Southern Italy, demonstrating how beliefs about the dead and rites of passage are widespread and have endured, in various forms, for millennia. This tradition continues to thrive in these lands, remaining apart from commercialization and staying true to a culture that celebrates this realm with respect and reverence.

The Bagnarole: Witnesses of the Belle Époque in Italy and Salento

The Belle Époque in Italy was a period of prosperity and innovation, spanning from the late 19th century until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Characterized by social, economic, and cultural changes, this period coincided with industrial development, technological progress, and artistic renewal. Italy saw an acceleration of industrialization, an expansion of railway infrastructures, and a growth of cities as economic and innovation centers. Technological advancements such as electricity, the telephone, and the automobile transformed the country, while the growth of the urban bourgeoisie and middle class led to improvements in living conditions. Culturally, the Liberty artistic movement influenced architecture and design, while literature, music, and theater flourished. Italian cities became important tourist destinations for the European elite, contributing to the development of tourism.

In particular, seaside tourism began to take hold, transforming the coasts into leisure spots for the bourgeoisie and aristocracy.

It was in this context that the “bagnarole” were born, iconic structures of this new era of leisure and well-being.

The Bagnarole: A Dive into the Past of the Belle Époque

The "bagnarole," mostly wooden mobile cabins mounted on wheels, were used to allow bathers to change and immerse themselves in the sea waters away from prying eyes. These structures, pulled by horses to the shore or even halfway into the water, offered discreet shelter in line with the decorum norms of the time, which required that women could enter and exit the water without being seen.

The "bagnarole," mostly wooden mobile cabins mounted on wheels, were used to allow bathers to change and immerse themselves in the sea waters away from prying eyes. These structures, pulled by horses to the shore or even halfway into the water, offered discreet shelter in line with the decorum norms of the time, which required that women could enter and exit the water without being seen.

Born in the United Kingdom at the end of the 18th century, the "bagnarole" quickly spread throughout Europe during the Belle Époque, also becoming widely popular in Italy, especially in seaside resorts frequented by nobility and wealthy bourgeoisie seeking relaxation and social life.

Bagnarole in Salento: The Elegance of Santa Maria di Leuca

The jewel of summer vacations in Salento at that time was Santa Maria di Leuca.

The jewel of summer vacations in Salento at that time was Santa Maria di Leuca.

The fashion for summer stays in coastal areas, which pervaded all social classes, led to the development of different types of "bagnarole":

- Bagnarola a conca: This was the type for the common people, essentially a natural hollow between rocks by the sea used by those who, not knowing how to swim, were looking for a safe place. Besides this natural "hole," there were also artificial hollows, indicating attempts at larger excavations.

- Uncovered bagnarola : A kind of bathtub carved into the cliff, generally quadrangular in shape. Almost all had a ladder to descend into the water, which entered through two openings and reached a very low level, so that both children and adults who could not swim could bathe. Originally, these "bagnarole" were reserved, so it was difficult to access them without permission. Each had the name of its owner, who belonged to a middle social level.

Wooden bagnarola: Dug near the shore like the uncovered "bagnarola," with a quadrangular shape, sea access openings, and stone ladders, it served as the base for a wooden covering. Practically, the lower part, that is, the base, had water; then the wooden floor with ladders to descend into the water, followed by all-wooden side panels that closed the structure. The function of the wooden "bagnarola" was to create a private, secluded environment sheltered from the sun. These "bagnarole" no longer exist today; they were active until the 1960s. These "bagnarole" were usually reserved for upper bourgeoisie families. The structure would be set up at the beginning of the summer season and removed with the first autumn storms in early October.

Wooden bagnarola: Dug near the shore like the uncovered "bagnarola," with a quadrangular shape, sea access openings, and stone ladders, it served as the base for a wooden covering. Practically, the lower part, that is, the base, had water; then the wooden floor with ladders to descend into the water, followed by all-wooden side panels that closed the structure. The function of the wooden "bagnarola" was to create a private, secluded environment sheltered from the sun. These "bagnarole" no longer exist today; they were active until the 1960s. These "bagnarole" were usually reserved for upper bourgeoisie families. The structure would be set up at the beginning of the summer season and removed with the first autumn storms in early October.- Stone bagnarole: The fundamental structure was the same, a section of the cliff carved into a quadrangular shape with two openings to the sea. Covered by a stone construction, it was accessed through a side door leading to a landing from which one could descend into the water via a stone ladder. The structure’s purpose was to offer the possibility of undressing and having a completely private environment. Therefore, a cabin that guaranteed a covered bath without being seen and maintaining the fair skin tone, as was the fashion of the time. These generally had a circular, hexagonal, or even dodecagonal shape. Located right by the sea, almost always in front of the villa to which they belonged. These were also a sign of nobility. This is because, starting from the late 1800s, numerous villas in Liberty and Moorish styles began to be built in Santa Maria di Leuca, in line with the era’s standards, as a representation of the growing power of the upper bourgeoisie and nobility. The villa owners could afford the luxury of reserving a piece of the coast and building their noble cabin in the style and color of their villa. It was a sign of "ownership" and "identity."

Today, only three stone "bagnarole" remain: two large ones, those of Villa Meridiana and Villa Fuortes, and a small one built on unexcavated rock near the pier (the former English dock).

Other examples of "bagnarole" in the Salento area can be found in Santa Caterina (a marina of Nardò) and Marina Serra (a marina of Tricase).

"The Bathing Room" in Santa Caterina di Nardò is accessible from two side openings to the room, one of which must have been the main entrance because the door hinges that closed the entrance are still visible; the other is very rugged and difficult to reach. But the most suggestive entrance is the semi-submerged hole that allows access from the sea. One holds their breath, takes two strokes, and is transported from a crowded beach to a place suspended out of time.

"The Bathing Room" in Santa Caterina di Nardò is accessible from two side openings to the room, one of which must have been the main entrance because the door hinges that closed the entrance are still visible; the other is very rugged and difficult to reach. But the most suggestive entrance is the semi-submerged hole that allows access from the sea. One holds their breath, takes two strokes, and is transported from a crowded beach to a place suspended out of time.

In Marina Serra, we find a "bagnarola a conca," known as the "Grotta dell’amore or degli innamorati" (Cave of Love or Lovers), and the "Grotta Spinchialuru," where near the opening, a cavity was created for undisturbed bathing.

Bagnarole in the Rest of Europe: An International Phenomenon

Beyond Italy, the "bagnarole" also became a symbol of the era in other European locations. In the United Kingdom, for example, the "bagnarole" were ubiquitous along the coasts of Scarborough, Brighton, and Whitby. In France, they were found in Deauville and Trouville on the Normandy coast, where they were used by French aristocrats and the Parisian bourgeoisie. In Belgian seaside resorts like Ostend, along the Baltic Sea coast in Germany, and on the elegant beaches of Scheveningen in the Netherlands, "bagnarole" became an integral part of the landscape.

found in Deauville and Trouville on the Normandy coast, where they were used by French aristocrats and the Parisian bourgeoisie. In Belgian seaside resorts like Ostend, along the Baltic Sea coast in Germany, and on the elegant beaches of Scheveningen in the Netherlands, "bagnarole" became an integral part of the landscape.

Each country adapted them to its style and needs, but they all shared the same purpose: to allow discreet sea bathing while respecting the era’s strict moral standards.

The Bagnarole Today: A Historical and Cultural Rediscovery

Over time, the "bagnarole" lost their original function and were slowly abandoned or destroyed. However, in recent years, there has been a renewed interest in these iconic structures, which represent a window into the past and the elegance of the Belle Époque.

Over time, the "bagnarole" lost their original function and were slowly abandoned or destroyed. However, in recent years, there has been a renewed interest in these iconic structures, which represent a window into the past and the elegance of the Belle Époque.

In some places in Europe, such as the British coast or the beaches of Deauville, some original "bagnarole" have been restored and preserved as tourist attractions and historical testimonies. In Italy, particularly, the recovery of "bagnarole" has been more sporadic, but there are examples of faithful reconstructions in places like Santa Margherita Ligure or in museums related to sea culture.

In Santa Maria di Leuca, although many original "bagnarole" have been lost, interest in this historical heritage remains alive. Some restoration and recovery projects have been initiated to preserve the memory of these fascinating cabins. In 2015, the "bagnarola" of Villa La Meridiana was severely damaged by a violent storm, creating a breach in one of the walls, which was promptly repaired. The rediscovery of the "bagnarole" is not just a way to enhance an architectural element, but also to relive and tell a story of elegance, traditions, and love for the sea.

The "bagnarole" represent much more than simple mobile structures: they are witnesses of an era when leisure, well-being, and elegance were fundamental values. Their rediscovery and enhancement offer a fascinating journey back in time, allowing us to relive the atmosphere of the Belle Époque and appreciate the history of Europe's seaside resorts, including the enchanting ones of Salento.

As interest in the "bagnarole" continues to grow, it becomes increasingly evident that their charm is not only tied to the past but also to the desire to reclaim a refined lifestyle linked to the pleasure of small things. Who knows, maybe one day we will see them return to our beaches as a symbol of a time that still fascinates and inspires.

Guide to financing for buying and renovating your home in Salento

If you are thinking of buying a house in Salento and need financing, there are some essential steps that will help you navigate the process smoothly, allowing you to achieve your goals.

First of all, it is important to carefully assess your budget and the total costs of the purchase. This means determining how much you are willing to spend on the house itself, but also considering all the additional expenses that often accompany a real estate purchase: from notary fees to taxes, from real estate agency commissions to any renovation work. Having a complete picture of these costs will help avoid surprises and plan your finances realistically.

Next, you need to learn about the different types of financing available to choose the one that best suits your needs.

The Mortgage

If you don't have most of the amount needed to purchase the property, you can apply for a mortgage from a financial institution. This is a financing contract through which the beneficiary (the one who applied for the mortgage) obtains the amount that will allow them to purchase the desired property. The borrower commits to repay the obtained amount to the financial institution, plus any interest, through a certain number of installments, whose amount and duration are defined by the amortization schedule accepted at the time of signing the contract.

All mortgage contracts include some essential elements: the chosen interest rate, the duration, the amortization schedule, and any additional guarantees besides the mortgage.

How much money should you have in the bank to apply for a mortgage? To choose the financing option, you first need to know the cost of the house and, therefore, the amount you need to obtain from the bank to complete the purchase. However, keep in mind that the maximum loan amount you can obtain is up to 80% of the property's value; you must have the remaining 20% available. Some institutions also offer mortgages up to 100% of the property value, but under more onerous conditions. Moreover, they require the customer to provide additional guarantees besides the mortgage.

The general rule of Italian banks is that the mortgage installment must not exceed 30% of the applicant's disposable income. If the mortgage is co-signed, the combined income of both applicants is considered. For example, with a salary of €1,200 per month, considering the 30% rule, the maximum monthly installment would be around 400 euros.

There are different types of mortgages based on the applied interest rate. Specifically, in a "fixed-rate mortgage," the interest rate does not change throughout the loan term, and the installments always remain the same. In a "variable-rate mortgage," the installment varies according to the interest rate trend, which is, in turn, linked to a market parameter. Therefore, the amount payable each month can fluctuate. Then there is the "mixed mortgage," which allows the borrower to switch from a fixed rate to a variable rate and vice versa. There is also the "capped mortgage," where a maximum limit is set beyond which the installment cannot rise. This way, from the outset of the amortization schedule, the borrower is guaranteed that the installment cannot increase to unaffordable levels over time. The fluctuation of the interest rate, which can rise or fall over time, may cause the mortgage amortization schedule to lengthen or shorten. Finally, there is the "introductory rate mortgage," where the bank and the client agree on a reduced rate for an initial period. Once this period expires, the current fixed or variable rate will be applied.

The amortization schedule is how the mortgage loan will be repaid to the bank. You can choose between a "French amortization schedule," which is the most common and provides that interest payments decrease over time while capital payments increase. Therefore, in the first installments of the mortgage, the interest payments will be higher, and the capital payments will be lower. The installment remains constant for the entire duration of the mortgage. There is also a "growing installment schedule," where the installments increase in amount every month. The "free amortization schedule," where the installments consist only of the interest payments, and the capital can be repaid within predetermined deadlines. As the repayments occur, the interest payments are recalculated. Lastly, there is the "fixed-rate and variable-duration schedule," where the installment remains constant, but interest rate variations determine the extension or shortening of the repayment plan.

Therefore, the amortization schedule will also determine the duration of the mortgage installments, from 5 to 30 years, and some banks go up to 40 or even 50 years.

When a bank grants a mortgage, it requires a mortgage lien on the house as collateral. In practice, the mortgage allows the bank to have two rights on the property: the right to take possession of the house if the mortgage cannot be repaid and the right to obtain the money from selling the house before other creditors. This way, the bank protects itself in case of non-payment or delays in mortgage installments. The mortgage is formalized by a notary and registered in the Real Estate Registers. Even with a mortgage on the house, you remain the owner and can continue to use it as you wish.

There are different types of mortgages depending on the type of real estate operations the customers need to undertake. Alongside the classic mortgage for purchase, there is also the mortgage for purchase and renovation, which in a single solution provides liquidity for both buying the house and carrying out the necessary works. This mortgage is essentially divided into two parts: one part is intended for the purchase of the primary residence, while the other is intended for the payment of the works. The first part is calculated based on the property's value, while the second part is based on the work estimate. The disbursement of money occurs in various phases: at the time of purchase and based on the progress of the works.

Not to forget the completion of construction mortgage, also called a building mortgage, granted by banks up to 80% of the cost required for construction to provide liquidity for the completion of the works. The duration is variable, averaging 30 years, and the conditions are different from those of a classic mortgage. It does not involve the complete disbursement of the loan in a single tranche but progressively depending on the progress of the works, and the documentation and guarantees required are greater than for other types of mortgages.

The Loan

Another form of available financing is a loan. It can be used to pay for current house expenses or renovation, but rarely for the actual purchase of the property.

It does not allow for the use of the tax benefits provided by financial law for those buying a primary residence and has a shorter duration than a mortgage (usually around 48/60 months).

It involves a shorter process for the request and approval, and it often takes just 15 days to obtain it. It deals with smaller sums than mortgages and requires real guarantees, such as a mortgage on the property, to cover the financing.

It is almost always granted in the form of a fixed-rate loan with installments and interest.

Mortgage or Loan?

Depending on your needs, you must evaluate whether they can be met with a mortgage or a loan.

The Case of Home Renovation

It is true that we almost always face a mandatory choice between a mortgage and a loan. However, in some cases, it is possible to freely choose between the two options. This is the case for renovations with an amount ranging between 30,000 and 70,000 euros.

Why this overlap? Because the maximum granted for personal loans is usually 70,000 euros. At the same time, the minimum granted for a mortgage is 30,000 euros.

How to compare these two options? We have only one valid way to do it: focus on the costs of each solution. A personal loan for an amount between 30,000 and 70,000 euros usually has an APR of around 5.5%.

A mortgage, on the other hand, offers rates around 2%. Of course, one should distinguish between fixed and variable rates and based on the individual case of the applicant. In general, however, they prove to be a significantly less expensive solution. This is especially true with the very low IRS and Euribor rates currently available on the market.

Not only that, but we must also consider that, in the case of renovating a primary residence, we can take advantage of all the benefits provided by the current financial law.

The advantage of personal loans, however, is there. Although more expensive and less convenient fiscally, they are usually granted more quickly.

Therefore, everyone has their preferred solution based on their priorities and the quotes received from banks and financial institutions.

In this article, we have seen how, thanks to financing, it is finally possible to realize the dream of buying and renovating a house in Salento, even if you don't immediately have all the necessary funds. With a mortgage or a loan, you have the opportunity to turn your dream of having a home in this beautiful land into reality, adapting it to your needs and style.

Between clay and dreams: salentine ceramics, ancient roots and architectural visions

Salentine ceramics, one of the most authentic and ancient expressions of Apulian craftsmanship, represent a cultural heritage of inestimable value. This artisanal tradition, born centuries ago, has evolved over the ages in forms, styles, and uses, while always maintaining a deep connection with the local territory and architecture.

The word "ceramics" itself has Greek origins, from "kéramos," which means "potter's clay." Due to its great versatility, this material has been used over the centuries to produce various objects, crafted by the skilled hands of expert artisans and ready to be decorated with a variety of techniques.

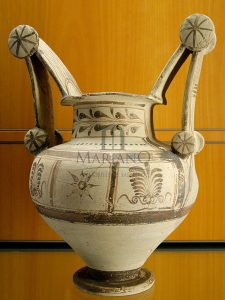

The origins of Salentine ceramics date back to prehistoric times when local populations began shaping clay to create everyday utensils and ritual objects. Among the most celebrated traditional pottery for its beauty, the Messapian production, typical of Salento between the eighth and third centuries BC, holds a place of honor. The Messapians, an ancient population of Illyrian origin, created vases (notably ollas and trozzelle) with increasingly complex decorations, starting with geometric motifs in the early period and later influenced by Greek patterns. Soon, Messapian vases began to be fully decorated, including floral and figurative motifs, before returning to geometric and monochromatic decorations in the third period, this time with clear Hellenic influences. New forms of vases also emerged, such as the pyxis or the krater, but the typical trozzella, with its ovoid body and ribbon-like handles equipped with four characteristic wheels, remained the truest and purest expression of Messapian art, along with types like the pignata, used for cooking typical Salentine dishes, and the capase, for storing water.

The origins of Salentine ceramics date back to prehistoric times when local populations began shaping clay to create everyday utensils and ritual objects. Among the most celebrated traditional pottery for its beauty, the Messapian production, typical of Salento between the eighth and third centuries BC, holds a place of honor. The Messapians, an ancient population of Illyrian origin, created vases (notably ollas and trozzelle) with increasingly complex decorations, starting with geometric motifs in the early period and later influenced by Greek patterns. Soon, Messapian vases began to be fully decorated, including floral and figurative motifs, before returning to geometric and monochromatic decorations in the third period, this time with clear Hellenic influences. New forms of vases also emerged, such as the pyxis or the krater, but the typical trozzella, with its ovoid body and ribbon-like handles equipped with four characteristic wheels, remained the truest and purest expression of Messapian art, along with types like the pignata, used for cooking typical Salentine dishes, and the capase, for storing water.

During the Greco-Roman period, ceramic production in the Salento region was enriched with more sophisticated techniques and decorations, influenced by contacts with Mediterranean civilizations. These cultural exchanges contributed to the development of a ceramic tradition characterized by a great variety of forms and decorative motifs.

With the advent of the Middle Ages and then the Renaissance, Salentine ceramics continued to thrive, establishing themselves as a refined art. Artisan workshops multiplied in the main cities of Salento, such as Lecce, Grottaglie, and Cutrofiano, where artisans experimented with new glazes and decorative techniques. During the Baroque period, Salentine ceramics reached the pinnacle of their artistic expression, thanks to the richness of floral motifs and mythological figures.

workshops multiplied in the main cities of Salento, such as Lecce, Grottaglie, and Cutrofiano, where artisans experimented with new glazes and decorative techniques. During the Baroque period, Salentine ceramics reached the pinnacle of their artistic expression, thanks to the richness of floral motifs and mythological figures.

Over the centuries, Salentine ceramics have undergone continuous evolution, adapting to new aesthetic and functional needs. Production has expanded from creating everyday objects, such as plates, vases, and pots, to producing decorative elements for architecture, such as majolica tiles and rosettes. The blending of other Italian and European ceramic traditions has enriched the Salentine stylistic repertoire, leading to the creation of unique pieces that combine tradition and innovation.

Today, Salentine ceramics keep traditional artisanal techniques alive while also embracing new technologies and contemporary design trends. Many artisan workshops, often family-run, continue to produce ceramics using ancient methods but with an eye on modern market demands.

In contemporary usage, Salentine ceramics are applied in various contexts, both as functional and decorative elements. Ceramic objects are appreciated for their beauty and their ability to tell the story and culture of Salento. In addition to traditional kitchen items, Salentine ceramics are used to create furniture accessories, such as lamps, tables, and tiles, adding a touch of elegance and authenticity to spaces.

Ceramic craftsmanship is also an important economic sector for the region, attracting cultural tourism. Fairs and markets dedicated to Salentine ceramics draw visitors from all over the world, eager to discover and purchase unique, handmade pieces.

Among the most characteristic elements are:

The Pumo

The name and the reasons for the production of the pumo, which has become one of the most distinctive symbols of the artisanal tradition, can be traced back to the history of ancient Rome when the cult of Pomona, the goddess of fruits, was celebrated. The word pumo derives from the Latin "pomum," meaning "fruit."

The name and the reasons for the production of the pumo, which has become one of the most distinctive symbols of the artisanal tradition, can be traced back to the history of ancient Rome when the cult of Pomona, the goddess of fruits, was celebrated. The word pumo derives from the Latin "pomum," meaning "fruit."

Its shape recalls a bud enclosed by four acanthus leaves, symbolizing life being renewed. It is a symbol of prosperity and fertility, but also of chastity, immortality, and resurrection. Additionally, it has an apotropaic function, acting as a sort of amulet capable of warding off evil and bad luck. For these reasons, this artifact initially spread among the noble families of Puglia, who used it as a decorative element on the facades of noble mansions and on wrought iron railings, before becoming popular among the rest of the population, including peasants.

and fertility, but also of chastity, immortality, and resurrection. Additionally, it has an apotropaic function, acting as a sort of amulet capable of warding off evil and bad luck. For these reasons, this artifact initially spread among the noble families of Puglia, who used it as a decorative element on the facades of noble mansions and on wrought iron railings, before becoming popular among the rest of the population, including peasants.

The pumi of the nobility were distinguished from those of others. In fact, the lords of the town would personalize them with heraldic symbols and a varying number of leaves around the bud, as a testament to the notoriety, authority, and wealth of their family. The function of the pumo is not to chase away bad luck or evil; it precedes bad luck and keeps it at bay, acting as an impenetrable barrier to evil. The pumo is therefore a good luck charm, which, according to tradition, should not be purchased but gifted or received as a gift.

Capase or Capasoni

The farmers of Puglia and Salento used these beautiful terracotta containers for various purposes, mainly to store liquids like extra virgin olive oil, water, or wine. The value of these containers was that they could preserve the characteristics of the contained liquid, particularly its temperature. The name capasa comes from the Latin "capax capacis," meaning "capable," referring to the often large capacity of these containers and their usefulness in storing liquids. The capasa is also known as capasone, with an augmentative meaning. In past centuries, the larger capase were used instead of barrels during the grape harvest. Just a few dozen of the largest ones (with a capacity of at least 200 liters) were enough to store wine. Usually, the mouth of the capasoni was sealed with a plug made of lime and ash. Near the base of the capasone, about twenty centimeters from the bottom, there was a drainage spout to which a sort of tap was attached, called "cannedda." Sometimes, a small cork plug, known as "pipulu," was used instead. This made it easy to obtain the right amount of wine or oil by bringing a container close to the cannedda.

The farmers of Puglia and Salento used these beautiful terracotta containers for various purposes, mainly to store liquids like extra virgin olive oil, water, or wine. The value of these containers was that they could preserve the characteristics of the contained liquid, particularly its temperature. The name capasa comes from the Latin "capax capacis," meaning "capable," referring to the often large capacity of these containers and their usefulness in storing liquids. The capasa is also known as capasone, with an augmentative meaning. In past centuries, the larger capase were used instead of barrels during the grape harvest. Just a few dozen of the largest ones (with a capacity of at least 200 liters) were enough to store wine. Usually, the mouth of the capasoni was sealed with a plug made of lime and ash. Near the base of the capasone, about twenty centimeters from the bottom, there was a drainage spout to which a sort of tap was attached, called "cannedda." Sometimes, a small cork plug, known as "pipulu," was used instead. This made it easy to obtain the right amount of wine or oil by bringing a container close to the cannedda.

Capasoni were not only used for agricultural work but also for transporting liquids back and forth across the Mediterranean. They were key players in trade for a long time, even to the Middle and Far East.

Today, capase and capasoni have come back into fashion, and there is a large market revolving around the search for old specimens and their revaluation. It is common to see them at the entrances of prestigious tourist resorts, in the courtyards of many noble villas, and in gardens and outdoor areas.

The Rooster

The undisputed protagonist of the decoration of Apulian ceramics, the rooster can be found on many everyday objects, most of which are used at the table during meals. Its history has ancient and extraordinary origins, and the rooster symbolizes the figure of Mercury, the god of commerce, profit, and eloquence. The rooster is therefore identified as a sacred animal, which, besides representing Mercury, can be linked to other important symbols. It is considered almost a domestic animal, capable of driving away all negative energies and malice from one's home. Lastly, but not least importantly, the famous Apulian rooster is considered a symbol of fertility.

The bond between Salentine ceramics and architecture is particularly strong.

Since the Baroque period, majolica tiles and decorative ceramic panels have been used to embellish churches, palaces, and noble residences. Ceramics became a distinctive element of Lecce Baroque, with its vibrant colors and ornamental motifs enriching the facades of buildings.

Even in contemporary architecture, Salentine ceramics continue to play an important role. Architects and designers often choose ceramic materials for their aesthetic and functional qualities, such as durability and ease of maintenance. Ceramic tiles are used both indoors and outdoors, creating continuity between tradition and new trends in sustainable architecture.

Salentine ceramics, with their ancient roots and continuous evolution, represent a symbol of the culture and identity of Salento. Their relationship with architecture and their current use testify to the ability of this tradition to renew and adapt to the times while preserving its authenticity. The future of Salentine ceramics looks bright, with new generations of artisans ready to carry on this heritage with passion and creativity.

Apotropaic Architecture in Salento: Symbols and Secrets of a Millenary Tradition

Apotropaic architecture in Salento represents a fascinating and meaningful tradition, which intertwines symbolism, religiosity and popular culture. This type of architecture, characterized by elements designed to protect homes and places of worship from evil influences, finds its roots in ancient practices and has developed over the centuries, adapting to the cultural and social changes of the region.

The term “apotropaic” derives from the Greek “apotrépein”, which means “to drive away”, and refers to objects, symbols or architecture designed to drive away or keep away evil. In Salento, as in many other regions of the Mediterranean, these practices are deeply rooted in the local culture and have their origins in antiquity.

The influences of the apotropaic architecture of Salento are to be found in the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, which had already developed a series of rituals and symbols to protect their homes from evil spirits. Over time, these practices have merged with local religious and popular beliefs, giving rise to a unique architectural tradition.

During the Middle Ages, the apotropaic architecture of Salento took on a more defined connotation, with the introduction of decorative and structural elements specifically designed for protection from the forces of evil.

The main elements of apotropaic architecture are many:

- Mascarons and Stone Heads, or grotesque masks or faces carved in stone, often placed above doors or on the corners of buildings. It was believed that these frightening images could ward off evil spirits or the “evil eye”, or the bad

omen resulting from a malevolent look. One of the most characteristic examples is the “Loggia degli Sberleffi”, located in Giuliano di Lecce, built in 1609 on 15 corbels representing different figures that mock, precisely, the evil spirits that would like to disturb the domestic peace, thus driving them away with their grimaces, tongues and long faces. Some of the figures have an appearance that borders on the grotesque, elf ears, drooping cheeks, enormous moustaches. Others are extremely nice. They certainly represent different moments in a man's life, from faces that range from youth to old age, an aspect also highlighted by the camouflage and facial features.

omen resulting from a malevolent look. One of the most characteristic examples is the “Loggia degli Sberleffi”, located in Giuliano di Lecce, built in 1609 on 15 corbels representing different figures that mock, precisely, the evil spirits that would like to disturb the domestic peace, thus driving them away with their grimaces, tongues and long faces. Some of the figures have an appearance that borders on the grotesque, elf ears, drooping cheeks, enormous moustaches. Others are extremely nice. They certainly represent different moments in a man's life, from faces that range from youth to old age, an aspect also highlighted by the camouflage and facial features.

- Fairies, beautiful and graceful sculptures, which instead have their origins in the oral tradition of the fable, also placed outside the buildings for protective purposes. The most evident