Amid the folds of the Salento landscape, in places often far from the spotlight of conventional tourism, a phenomenon is taking shape—one that blends urban creativity, collective memory, and architectural regeneration: street art. Not only in Lecce, but also in small towns like Presicce, Tricase, Galatina, Parabita, and Nardò, the walls tell new stories, engage with local identity, and reinterpret the forms of the territory using contemporary languages.

Urban Art and Architecture: A Dialogue Woven into Place

Street art in Salento doesn’t impose itself; it takes root in the existing urban fabric. Wall surfaces—be they façades of old homes, school perimeters, or disused agricultural silos—become canvases for visual narratives that do not erase but transform. This dialogue between painted gesture and architectural material is especially evident in villages where Lecce stone, dry stone walls, and courtyard houses define the collective imagination.

Lecce: The 167 B Street Art Project

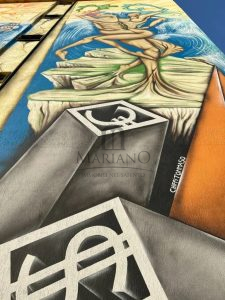

One of the most emblematic examples of the bond between public art and urban regeneration is the 167 B Street Art Project in Lecce. Initiated by the cultural association 36° parallelo, the project transformed the peripheral neighborhood of 167 B into an open-air gallery. International artists such as Millo, Zed1, Manu Invisible, and Chekos’art created monumental murals on building façades, tackling themes such as coexistence, environment, and personal growth.

In this context, urban art takes on an almost architectural role: it redefines the perception of space, highlighting areas once considered marginal. It is not mere decoration but a tool of urban transformation.

Galatina, Tricase, Parabita: Small Towns, Big Visions

While Lecce may represent the metropolitan face of Salento’s street art, the inland and coastal towns offer a diffused laboratory where art, architecture, and local memory intersect in original ways.

In Galatina, several artists have reimagined walls and leftover spaces with works inspired by religious tradition and popular culture. In Tricase, the Libera Compagnia collective activated urban workshops involving citizens, students, and architects in creative regeneration projects—many of them temporary, created during summer festivals, yet powerful in their symbolic impact.

In Parabita, the project RigenerAzioni Visive turned abandoned walls into storytelling spaces. Here, street art becomes civic education and shared design, strengthening the bond between the urban landscape and its community.

Presicce: Art that Respects the Stone

In the village of Presicce, listed among Italy’s Most Beautiful Villages, street art adopts subtle tones that harmonize with the built environment. Murals appear on stone walls, courtyard homes, and narrow alleys, evoking agricultural themes, collective memories, and local symbols. The Presicce Street Art Experience project, partly site-specific and temporary, engaged young Salento-based artists in an effort to match artistic expression with historic architecture.

Artist Marina Mancuso, originally from Presicce and recently returned after years in L’Aquila, has chosen an autonomous path: transforming corners of urban decay into works of art. Wooden or metal doors, old phone booths, and electrical cabinets become her canvases. Her recurring subjects include angels, sacred icons, and rural scenes inspired by cemetery monuments.

“I’ve been working on this project for months, and my goal is to rehabilitate spaces abandoned to neglect.”

For Marina, it’s a true mission.

“I intervene in areas prone to decay or vandalism. I try to cover vulgar words, insults, and graffiti with beauty.”

But she makes a point: “I never touch beautiful antique doors or the natural crusts of the walls. I just wish everything that belongs to the community were cared for like a precious asset, not ruined.”

Nardò: The Voice of the Walls

Nardò: The Voice of the Walls

Nardò, one of the most dynamic towns in Salento, also stands out for the vitality of its street art scene, especially in its outer neighborhoods. Here, urban art becomes a chance encounter that surprises and provokes reflection—walls speaking of justice, equality, listening, respect, and dignity.

Among the most meaningful works is Stefano Bergamo’s mural at the Gabelli School: a girl seen from behind, with a dog and a cat, created to raise awareness about stray animals. Near the public housing units, a mural pays tribute to Salvatore Napoli Leone, a local entrepreneur and inventor of the modern ice cream cone wafer.

In the 167 neighborhood, the regeneration project brought high-caliber murals to building façades. The mural Brocche di ceramica (Ceramic Pitchers) by Spanish artist Manolo Mesa recalls Nardò’s historic ceramic tradition, active from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

Nearby, a large flower inspired by the flora of the Porto Selvaggio Natural Park, painted by Puerto Rican artist Natalia Rodriguez (2Bleene), stands out. Tommaso Chiffi, in Rinascita (Rebirth), portrays nature’s revenge over mankind; while Hitnes, a Roman artist, tells the story of the struggle between living and extinct animals, prompting reflection on the historical legacy of the land.

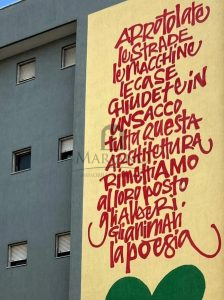

Lastly, Marta Lagna’s mural in the market square features a poem by Franco Arminio:

Lastly, Marta Lagna’s mural in the market square features a poem by Franco Arminio:

“Roll up the streets, the cars, the houses

Stuff all this architecture into a sack

Let’s restore trees, love, and poetry to their place”

An Evolving Heritage

Not all interventions are permanent. Some were created as part of festivals or artist residencies and were designed to last just a season. Yet even these ephemeral experiences contribute to redefining the relationship between community and urban space, offering new narratives and future possibilities.

Street art in Salento is not mere ornamentation. It is a political, social, and architectural act, restoring centrality to the margins, visibility to small towns, and dignity to forgotten places. It is, in every respect, a form of contemporary, widespread architecture, able to speak both to the stones and to the people.