Halloween and the Ancient Traditions of Salento

Halloween is a celebration that originates from Celtic traditions, yet some of its customs have taken root in Southern Italy during the long Norman domination. What connects Halloween to Salento? Although this occasion with its eerie atmosphere stems from ancient Celtic traditions, not everyone is aware that in Salento and Southern Italy, similar rituals exist, influenced by the Norman period and ancient Christian traditions intertwined with pagan rites.

For the Celts, the night of October 31 marked the end of the year and the moment when Samhain, the Lord of Death and Winter, gathered the souls of the deceased, who briefly reunited with the living. To prevent evil spirits from entering the bodies of the living, villagers would extinguish the fires in their homes, only to relight them at nightfall to burn offerings and perform protective spells. For three days, the Celts wore animal skins to ward off unwanted spirits, a practice that influenced the modern tradition of costumes.

Similarly, the ancestors of Salento and Southern Italy engaged in rituals honoring the deceased from October 31 to November 2. In some areas of Southern Italy, gifts and sweets are still prepared for children, with stories that they were left by deceased relatives; in other places, tables are set for a dinner believed to be attended by the souls of loved ones. In various locations, bonfires made from broom branches are lit in public squares, and leftovers from dinners are left outside for the deceased.

Similarly, the ancestors of Salento and Southern Italy engaged in rituals honoring the deceased from October 31 to November 2. In some areas of Southern Italy, gifts and sweets are still prepared for children, with stories that they were left by deceased relatives; in other places, tables are set for a dinner believed to be attended by the souls of loved ones. In various locations, bonfires made from broom branches are lit in public squares, and leftovers from dinners are left outside for the deceased.

The use of carved and illuminated pumpkins, a symbol of Halloween, also has Italian roots. But why is this tradition more closely associated with America today? The answer is simple: the United States is largely populated by descendants of Europeans, and the significant emigration from Southern Italy in past centuries carried many of these customs across the ocean.  Traditions such as "trick or treat" are linked to Southern Italy and likely gained traction in America as immigrants, finding themselves in a Protestant society, felt the need to keep their ancient Catholic and pagan traditions alive.

Traditions such as "trick or treat" are linked to Southern Italy and likely gained traction in America as immigrants, finding themselves in a Protestant society, felt the need to keep their ancient Catholic and pagan traditions alive.

Salento has a long-standing tradition of celebrations related to the dead that, in certain villages, bear a striking resemblance to Halloween rituals. In villages like Miggiano, Supersano, and Presicce, it was common to prepare banquets for the souls as a sign of hospitality. People would leave typical sweets, such as boiled wheat and "bones of the dead" cookies, outside their doors or on tables to welcome their deceased loved ones. Children were also given sweets as gifts.

Today, in some villages, like Zollino, the traditions for the Night of the Dead are still very much alive. Families prepare tables at home adorned with lit candles, food, and drinks to welcome the deceased. This practice not only honors the departed but also symbolizes the welcoming of their souls. During this time, a procession heads to the village cemetery, where candles are lit to illuminate the path for the souls.

In Martano, another vibrant tradition involves creating home altars in memory of the deceased, accompanied by moments of reflection and family meals featuring typical dishes such as boiled wheat and dried figs. The lights and decorative candles that adorn homes and streets evoke the modern illuminated pumpkins of Halloween.

In Specchia, one of the oldest and most picturesque villages in Salento, women still prepare pupurati, spiced cookies offered to children as a symbol of continuity between generations. In ancient times, bonfires were lit here to drive away evil spirits and protect the harvest, serving as a way to honor the deceased and maintain a connection to the spiritual world.

The Salento traditions related to the dead uniquely intertwine with the celebrations we now associate with Halloween. While Halloween has evolved differently elsewhere, in Salento, the celebrations on November 1st and 2nd continue to pass down rituals that connect the living with the deceased, in a night experienced as a moment of reflection, respect, and memory.

One of the most suitable places to host legends of witches and mysterious spirits in Salento is the area between Giuggianello, Giurdignano, and Minervino di Lecce, where ancient "natural monuments" endure, still living in collective memory. This territory, often compared to the famous Stonehenge for its dolmens, menhirs, and sacred stones, is rich in suggestive tales revolving around nymphs, old witches, and fairies known as "scazzamurieddhi." The local countryside, with its invaluable heritage, has inspired countless fantastic stories and fairy tales passed down through generations.

For instance, the Massi della Vecchia were the home of a witch called "la striara," who, at sunset, cast spells against those who dared to desecrate that sacred place. Anyone who dared to look her in the face was forced to jump endlessly, as an old nursery rhyme recounts: "Zzumpa pisara cu la camisa te notte…" ("Jump, witch, in your nightgown"), to which the victim responds, "se scappu de stu chiaccu nu nci essu chiui de notte" (if I escape this trouble, I won’t go out at night again).

For instance, the Massi della Vecchia were the home of a witch called "la striara," who, at sunset, cast spells against those who dared to desecrate that sacred place. Anyone who dared to look her in the face was forced to jump endlessly, as an old nursery rhyme recounts: "Zzumpa pisara cu la camisa te notte…" ("Jump, witch, in your nightgown"), to which the victim responds, "se scappu de stu chiaccu nu nci essu chiui de notte" (if I escape this trouble, I won’t go out at night again).

In another version of the legend, aided by an ogre or her husband, the witch would turn into stone anyone who could not answer her questions. Many fell into her trap, lured by the promise of a hen that laid golden eggs, resulting in the area being scattered with rocks.

In this same region, tales speak of a challenge between young people and fairies. Once, farmers forbade their children from going among the large stones, saying that the "fairies," beautiful but dangerous creatures, could appear there.

In Uggiano, stories of witches abound, who, during the sabbat, would gather around a "walnut tree by the windmill." It is said that a local innkeeper, on a full moon night, left her husband alone to join them. When the man noticed the food and wine running low, knowing his wife’s secret, he went to the meeting place but mispronounced the formula and was lifted upside down into the air. His wife saved him by reciting a spell that made him fall, but since then, that tree has remained "secret" to avoid misfortune. It is said to be located near an ancient underground oil mill, but no one has ever been able to pinpoint its exact location.

In Soleto, on the other hand, it is said that the Guglia degli Orsini del Balzo, a fascinating tower adorned with monstrous figures, was built in a single night by Matteo Tafuri, a renowned philosopher and esotericist. For the feat, he allegedly summoned witches and spirits, but at dawn, some of them, surprised by the rooster's crow, were petrified in the tower.

In Soleto, on the other hand, it is said that the Guglia degli Orsini del Balzo, a fascinating tower adorned with monstrous figures, was built in a single night by Matteo Tafuri, a renowned philosopher and esotericist. For the feat, he allegedly summoned witches and spirits, but at dawn, some of them, surprised by the rooster's crow, were petrified in the tower.

Few may know that in Tricase, the so-called Chiesa Nuova (or Church of the Devils) was said to be the work of the Devil, who erected it in a single night after making a pact with the so-called "Old Prince," traditionally identified as Messer Jacopo Francesco Arborio Gattinara, a real historical figure. According to legend, the events unfolded as follows: around the end of the 17th century, Messer Jacopo decided to support the numerous farmers working and living in the countryside (who wanted to drive away the Malobre, or evil spirits) by building a new church outside Tricase, on the way to the sea, which was historically completed in 1685, with an octagonal shape, dedicated to the Madonna of Constantinople. To this end—through the enchanted "Book of Command"—he thought to summon the Devil himself, with the secret intent of mocking him. The challenge proposed by the nobleman of Tricase was accepted by the Devil, on the condition that, within the same church, as an insult and mockery to God, the Old Prince would then offer the consecrated host to a goat, a symbol of Satan. For this commitment, in addition, the Lord of Darkness would leave a chest filled with gold coins in the Chiesa Nuova. Once the pact was sealed and the church erected, the morning after, the Devil reminded the Old Prince of his promise, which he denied ever having made. Feeling mocked, the Devil vented his rage by opening a water ditch near the church (known to the locals as the Canale del Rio) and throwing the church bells into it, which still seem to resonate with their deep tolls underground during stormy days. And what about the chest with the gold coins? The Old Prince had the opportunity to find and open it, but inside, it seemed, were insignificant coins made of base metal or even stones.

Prince," traditionally identified as Messer Jacopo Francesco Arborio Gattinara, a real historical figure. According to legend, the events unfolded as follows: around the end of the 17th century, Messer Jacopo decided to support the numerous farmers working and living in the countryside (who wanted to drive away the Malobre, or evil spirits) by building a new church outside Tricase, on the way to the sea, which was historically completed in 1685, with an octagonal shape, dedicated to the Madonna of Constantinople. To this end—through the enchanted "Book of Command"—he thought to summon the Devil himself, with the secret intent of mocking him. The challenge proposed by the nobleman of Tricase was accepted by the Devil, on the condition that, within the same church, as an insult and mockery to God, the Old Prince would then offer the consecrated host to a goat, a symbol of Satan. For this commitment, in addition, the Lord of Darkness would leave a chest filled with gold coins in the Chiesa Nuova. Once the pact was sealed and the church erected, the morning after, the Devil reminded the Old Prince of his promise, which he denied ever having made. Feeling mocked, the Devil vented his rage by opening a water ditch near the church (known to the locals as the Canale del Rio) and throwing the church bells into it, which still seem to resonate with their deep tolls underground during stormy days. And what about the chest with the gold coins? The Old Prince had the opportunity to find and open it, but inside, it seemed, were insignificant coins made of base metal or even stones.

Lastly, the Grotta delle Striare in Santa Cesarea Terme, located along the cliff between Porto di Castro and Porto Miggiano, is a cave with an eerie atmosphere. Legend has it that witches gathered there to dance and brew potions. Those who venture into the cave speak of pungent odors and rocks carved into the shape of female hands with elongated nails, resembling those of a witch, particularly highlighted at sunset with the sulfurous vapors appearing to emanate from enchanted cauldrons.

Lastly, the Grotta delle Striare in Santa Cesarea Terme, located along the cliff between Porto di Castro and Porto Miggiano, is a cave with an eerie atmosphere. Legend has it that witches gathered there to dance and brew potions. Those who venture into the cave speak of pungent odors and rocks carved into the shape of female hands with elongated nails, resembling those of a witch, particularly highlighted at sunset with the sulfurous vapors appearing to emanate from enchanted cauldrons.

Thus, while Halloween has Celtic roots, it finds a surprising affinity in the customs of Salento and Southern Italy, demonstrating how beliefs about the dead and rites of passage are widespread and have endured, in various forms, for millennia. This tradition continues to thrive in these lands, remaining apart from commercialization and staying true to a culture that celebrates this realm with respect and reverence.

The Bagnarole: Witnesses of the Belle Époque in Italy and Salento

The Belle Époque in Italy was a period of prosperity and innovation, spanning from the late 19th century until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Characterized by social, economic, and cultural changes, this period coincided with industrial development, technological progress, and artistic renewal. Italy saw an acceleration of industrialization, an expansion of railway infrastructures, and a growth of cities as economic and innovation centers. Technological advancements such as electricity, the telephone, and the automobile transformed the country, while the growth of the urban bourgeoisie and middle class led to improvements in living conditions. Culturally, the Liberty artistic movement influenced architecture and design, while literature, music, and theater flourished. Italian cities became important tourist destinations for the European elite, contributing to the development of tourism.

In particular, seaside tourism began to take hold, transforming the coasts into leisure spots for the bourgeoisie and aristocracy.

It was in this context that the “bagnarole” were born, iconic structures of this new era of leisure and well-being.

The Bagnarole: A Dive into the Past of the Belle Époque

The "bagnarole," mostly wooden mobile cabins mounted on wheels, were used to allow bathers to change and immerse themselves in the sea waters away from prying eyes. These structures, pulled by horses to the shore or even halfway into the water, offered discreet shelter in line with the decorum norms of the time, which required that women could enter and exit the water without being seen.

The "bagnarole," mostly wooden mobile cabins mounted on wheels, were used to allow bathers to change and immerse themselves in the sea waters away from prying eyes. These structures, pulled by horses to the shore or even halfway into the water, offered discreet shelter in line with the decorum norms of the time, which required that women could enter and exit the water without being seen.

Born in the United Kingdom at the end of the 18th century, the "bagnarole" quickly spread throughout Europe during the Belle Époque, also becoming widely popular in Italy, especially in seaside resorts frequented by nobility and wealthy bourgeoisie seeking relaxation and social life.

Bagnarole in Salento: The Elegance of Santa Maria di Leuca

The jewel of summer vacations in Salento at that time was Santa Maria di Leuca.

The jewel of summer vacations in Salento at that time was Santa Maria di Leuca.

The fashion for summer stays in coastal areas, which pervaded all social classes, led to the development of different types of "bagnarole":

- Bagnarola a conca: This was the type for the common people, essentially a natural hollow between rocks by the sea used by those who, not knowing how to swim, were looking for a safe place. Besides this natural "hole," there were also artificial hollows, indicating attempts at larger excavations.

- Uncovered bagnarola : A kind of bathtub carved into the cliff, generally quadrangular in shape. Almost all had a ladder to descend into the water, which entered through two openings and reached a very low level, so that both children and adults who could not swim could bathe. Originally, these "bagnarole" were reserved, so it was difficult to access them without permission. Each had the name of its owner, who belonged to a middle social level.

Wooden bagnarola: Dug near the shore like the uncovered "bagnarola," with a quadrangular shape, sea access openings, and stone ladders, it served as the base for a wooden covering. Practically, the lower part, that is, the base, had water; then the wooden floor with ladders to descend into the water, followed by all-wooden side panels that closed the structure. The function of the wooden "bagnarola" was to create a private, secluded environment sheltered from the sun. These "bagnarole" no longer exist today; they were active until the 1960s. These "bagnarole" were usually reserved for upper bourgeoisie families. The structure would be set up at the beginning of the summer season and removed with the first autumn storms in early October.

Wooden bagnarola: Dug near the shore like the uncovered "bagnarola," with a quadrangular shape, sea access openings, and stone ladders, it served as the base for a wooden covering. Practically, the lower part, that is, the base, had water; then the wooden floor with ladders to descend into the water, followed by all-wooden side panels that closed the structure. The function of the wooden "bagnarola" was to create a private, secluded environment sheltered from the sun. These "bagnarole" no longer exist today; they were active until the 1960s. These "bagnarole" were usually reserved for upper bourgeoisie families. The structure would be set up at the beginning of the summer season and removed with the first autumn storms in early October.- Stone bagnarole: The fundamental structure was the same, a section of the cliff carved into a quadrangular shape with two openings to the sea. Covered by a stone construction, it was accessed through a side door leading to a landing from which one could descend into the water via a stone ladder. The structure’s purpose was to offer the possibility of undressing and having a completely private environment. Therefore, a cabin that guaranteed a covered bath without being seen and maintaining the fair skin tone, as was the fashion of the time. These generally had a circular, hexagonal, or even dodecagonal shape. Located right by the sea, almost always in front of the villa to which they belonged. These were also a sign of nobility. This is because, starting from the late 1800s, numerous villas in Liberty and Moorish styles began to be built in Santa Maria di Leuca, in line with the era’s standards, as a representation of the growing power of the upper bourgeoisie and nobility. The villa owners could afford the luxury of reserving a piece of the coast and building their noble cabin in the style and color of their villa. It was a sign of "ownership" and "identity."

Today, only three stone "bagnarole" remain: two large ones, those of Villa Meridiana and Villa Fuortes, and a small one built on unexcavated rock near the pier (the former English dock).

Other examples of "bagnarole" in the Salento area can be found in Santa Caterina (a marina of Nardò) and Marina Serra (a marina of Tricase).

"The Bathing Room" in Santa Caterina di Nardò is accessible from two side openings to the room, one of which must have been the main entrance because the door hinges that closed the entrance are still visible; the other is very rugged and difficult to reach. But the most suggestive entrance is the semi-submerged hole that allows access from the sea. One holds their breath, takes two strokes, and is transported from a crowded beach to a place suspended out of time.

"The Bathing Room" in Santa Caterina di Nardò is accessible from two side openings to the room, one of which must have been the main entrance because the door hinges that closed the entrance are still visible; the other is very rugged and difficult to reach. But the most suggestive entrance is the semi-submerged hole that allows access from the sea. One holds their breath, takes two strokes, and is transported from a crowded beach to a place suspended out of time.

In Marina Serra, we find a "bagnarola a conca," known as the "Grotta dell’amore or degli innamorati" (Cave of Love or Lovers), and the "Grotta Spinchialuru," where near the opening, a cavity was created for undisturbed bathing.

Bagnarole in the Rest of Europe: An International Phenomenon

Beyond Italy, the "bagnarole" also became a symbol of the era in other European locations. In the United Kingdom, for example, the "bagnarole" were ubiquitous along the coasts of Scarborough, Brighton, and Whitby. In France, they were found in Deauville and Trouville on the Normandy coast, where they were used by French aristocrats and the Parisian bourgeoisie. In Belgian seaside resorts like Ostend, along the Baltic Sea coast in Germany, and on the elegant beaches of Scheveningen in the Netherlands, "bagnarole" became an integral part of the landscape.

found in Deauville and Trouville on the Normandy coast, where they were used by French aristocrats and the Parisian bourgeoisie. In Belgian seaside resorts like Ostend, along the Baltic Sea coast in Germany, and on the elegant beaches of Scheveningen in the Netherlands, "bagnarole" became an integral part of the landscape.

Each country adapted them to its style and needs, but they all shared the same purpose: to allow discreet sea bathing while respecting the era’s strict moral standards.

The Bagnarole Today: A Historical and Cultural Rediscovery

Over time, the "bagnarole" lost their original function and were slowly abandoned or destroyed. However, in recent years, there has been a renewed interest in these iconic structures, which represent a window into the past and the elegance of the Belle Époque.

Over time, the "bagnarole" lost their original function and were slowly abandoned or destroyed. However, in recent years, there has been a renewed interest in these iconic structures, which represent a window into the past and the elegance of the Belle Époque.

In some places in Europe, such as the British coast or the beaches of Deauville, some original "bagnarole" have been restored and preserved as tourist attractions and historical testimonies. In Italy, particularly, the recovery of "bagnarole" has been more sporadic, but there are examples of faithful reconstructions in places like Santa Margherita Ligure or in museums related to sea culture.

In Santa Maria di Leuca, although many original "bagnarole" have been lost, interest in this historical heritage remains alive. Some restoration and recovery projects have been initiated to preserve the memory of these fascinating cabins. In 2015, the "bagnarola" of Villa La Meridiana was severely damaged by a violent storm, creating a breach in one of the walls, which was promptly repaired. The rediscovery of the "bagnarole" is not just a way to enhance an architectural element, but also to relive and tell a story of elegance, traditions, and love for the sea.

The "bagnarole" represent much more than simple mobile structures: they are witnesses of an era when leisure, well-being, and elegance were fundamental values. Their rediscovery and enhancement offer a fascinating journey back in time, allowing us to relive the atmosphere of the Belle Époque and appreciate the history of Europe's seaside resorts, including the enchanting ones of Salento.

As interest in the "bagnarole" continues to grow, it becomes increasingly evident that their charm is not only tied to the past but also to the desire to reclaim a refined lifestyle linked to the pleasure of small things. Who knows, maybe one day we will see them return to our beaches as a symbol of a time that still fascinates and inspires.

Guide to financing for buying and renovating your home in Salento

If you are thinking of buying a house in Salento and need financing, there are some essential steps that will help you navigate the process smoothly, allowing you to achieve your goals.

First of all, it is important to carefully assess your budget and the total costs of the purchase. This means determining how much you are willing to spend on the house itself, but also considering all the additional expenses that often accompany a real estate purchase: from notary fees to taxes, from real estate agency commissions to any renovation work. Having a complete picture of these costs will help avoid surprises and plan your finances realistically.

Next, you need to learn about the different types of financing available to choose the one that best suits your needs.

The Mortgage

If you don't have most of the amount needed to purchase the property, you can apply for a mortgage from a financial institution. This is a financing contract through which the beneficiary (the one who applied for the mortgage) obtains the amount that will allow them to purchase the desired property. The borrower commits to repay the obtained amount to the financial institution, plus any interest, through a certain number of installments, whose amount and duration are defined by the amortization schedule accepted at the time of signing the contract.

All mortgage contracts include some essential elements: the chosen interest rate, the duration, the amortization schedule, and any additional guarantees besides the mortgage.

How much money should you have in the bank to apply for a mortgage? To choose the financing option, you first need to know the cost of the house and, therefore, the amount you need to obtain from the bank to complete the purchase. However, keep in mind that the maximum loan amount you can obtain is up to 80% of the property's value; you must have the remaining 20% available. Some institutions also offer mortgages up to 100% of the property value, but under more onerous conditions. Moreover, they require the customer to provide additional guarantees besides the mortgage.

The general rule of Italian banks is that the mortgage installment must not exceed 30% of the applicant's disposable income. If the mortgage is co-signed, the combined income of both applicants is considered. For example, with a salary of €1,200 per month, considering the 30% rule, the maximum monthly installment would be around 400 euros.

There are different types of mortgages based on the applied interest rate. Specifically, in a "fixed-rate mortgage," the interest rate does not change throughout the loan term, and the installments always remain the same. In a "variable-rate mortgage," the installment varies according to the interest rate trend, which is, in turn, linked to a market parameter. Therefore, the amount payable each month can fluctuate. Then there is the "mixed mortgage," which allows the borrower to switch from a fixed rate to a variable rate and vice versa. There is also the "capped mortgage," where a maximum limit is set beyond which the installment cannot rise. This way, from the outset of the amortization schedule, the borrower is guaranteed that the installment cannot increase to unaffordable levels over time. The fluctuation of the interest rate, which can rise or fall over time, may cause the mortgage amortization schedule to lengthen or shorten. Finally, there is the "introductory rate mortgage," where the bank and the client agree on a reduced rate for an initial period. Once this period expires, the current fixed or variable rate will be applied.

The amortization schedule is how the mortgage loan will be repaid to the bank. You can choose between a "French amortization schedule," which is the most common and provides that interest payments decrease over time while capital payments increase. Therefore, in the first installments of the mortgage, the interest payments will be higher, and the capital payments will be lower. The installment remains constant for the entire duration of the mortgage. There is also a "growing installment schedule," where the installments increase in amount every month. The "free amortization schedule," where the installments consist only of the interest payments, and the capital can be repaid within predetermined deadlines. As the repayments occur, the interest payments are recalculated. Lastly, there is the "fixed-rate and variable-duration schedule," where the installment remains constant, but interest rate variations determine the extension or shortening of the repayment plan.

Therefore, the amortization schedule will also determine the duration of the mortgage installments, from 5 to 30 years, and some banks go up to 40 or even 50 years.

When a bank grants a mortgage, it requires a mortgage lien on the house as collateral. In practice, the mortgage allows the bank to have two rights on the property: the right to take possession of the house if the mortgage cannot be repaid and the right to obtain the money from selling the house before other creditors. This way, the bank protects itself in case of non-payment or delays in mortgage installments. The mortgage is formalized by a notary and registered in the Real Estate Registers. Even with a mortgage on the house, you remain the owner and can continue to use it as you wish.

There are different types of mortgages depending on the type of real estate operations the customers need to undertake. Alongside the classic mortgage for purchase, there is also the mortgage for purchase and renovation, which in a single solution provides liquidity for both buying the house and carrying out the necessary works. This mortgage is essentially divided into two parts: one part is intended for the purchase of the primary residence, while the other is intended for the payment of the works. The first part is calculated based on the property's value, while the second part is based on the work estimate. The disbursement of money occurs in various phases: at the time of purchase and based on the progress of the works.

Not to forget the completion of construction mortgage, also called a building mortgage, granted by banks up to 80% of the cost required for construction to provide liquidity for the completion of the works. The duration is variable, averaging 30 years, and the conditions are different from those of a classic mortgage. It does not involve the complete disbursement of the loan in a single tranche but progressively depending on the progress of the works, and the documentation and guarantees required are greater than for other types of mortgages.

The Loan

Another form of available financing is a loan. It can be used to pay for current house expenses or renovation, but rarely for the actual purchase of the property.

It does not allow for the use of the tax benefits provided by financial law for those buying a primary residence and has a shorter duration than a mortgage (usually around 48/60 months).

It involves a shorter process for the request and approval, and it often takes just 15 days to obtain it. It deals with smaller sums than mortgages and requires real guarantees, such as a mortgage on the property, to cover the financing.

It is almost always granted in the form of a fixed-rate loan with installments and interest.

Mortgage or Loan?

Depending on your needs, you must evaluate whether they can be met with a mortgage or a loan.

The Case of Home Renovation

It is true that we almost always face a mandatory choice between a mortgage and a loan. However, in some cases, it is possible to freely choose between the two options. This is the case for renovations with an amount ranging between 30,000 and 70,000 euros.

Why this overlap? Because the maximum granted for personal loans is usually 70,000 euros. At the same time, the minimum granted for a mortgage is 30,000 euros.

How to compare these two options? We have only one valid way to do it: focus on the costs of each solution. A personal loan for an amount between 30,000 and 70,000 euros usually has an APR of around 5.5%.

A mortgage, on the other hand, offers rates around 2%. Of course, one should distinguish between fixed and variable rates and based on the individual case of the applicant. In general, however, they prove to be a significantly less expensive solution. This is especially true with the very low IRS and Euribor rates currently available on the market.

Not only that, but we must also consider that, in the case of renovating a primary residence, we can take advantage of all the benefits provided by the current financial law.

The advantage of personal loans, however, is there. Although more expensive and less convenient fiscally, they are usually granted more quickly.

Therefore, everyone has their preferred solution based on their priorities and the quotes received from banks and financial institutions.

In this article, we have seen how, thanks to financing, it is finally possible to realize the dream of buying and renovating a house in Salento, even if you don't immediately have all the necessary funds. With a mortgage or a loan, you have the opportunity to turn your dream of having a home in this beautiful land into reality, adapting it to your needs and style.

The Fountains of Salento: discovering history through water

Fountains have a millennia-old history, rooted in the earliest human civilizations. Originally, they were simple structures designed to provide drinking water to communities, but over the centuries, they evolved into architectural and artistic elements of great significance.

The first documented fountains date back to the Mesopotamian and ancient Egyptian civilizations. These cultures developed techniques to channel water from rivers and natural springs to cities. In Egypt, royal gardens were often adorned with simple fountains, fed by channels that brought water from the Nile. In ancient Mesopotamia, fountains were an integral part of palace gardens and courtyards.

In ancient Greece and Rome, fountains were common in both public and private spaces. Roman fountains, in particular, were supplied by complex aqueduct systems that brought water from mountain springs to the cities. The fountains of Rome were often monumental, such as those in the Roman Forum, serving both as sources of drinking water and as decorative elements.

During the Middle Ages, fountains continued to be a common feature in European cities, often located in monastery courtyards and central city squares. In this period, many fountains had a primarily practical function, such as distributing drinking water or irrigating fields. However, in some cities, fountains also began to symbolize power and prestige, with elaborate decorations and religious sculptures.

In the Renaissance, fountains once again became highly valued artistic elements. Italy, in particular, saw the construction of numerous fountains that combined advanced hydraulic engineering and art. Renaissance fountains, such as those designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome, were often adorned with complex sculptures celebrating mythological deities, historical figures, and symbols of power.

During the Baroque period, fountains became even more theatrical and dramatic. Large Baroque fountains were often characterized by high water jets and complex water displays. Iconic examples of this period include the Triton Fountain in Rome and the fountains of Versailles in France.

With the advent of the industrial era, fountains continued to evolve, becoming symbols of technological progress. Modern fountains often use advanced pumping systems and lighting to create water displays that attract visitors. Today, fountains can be found in almost every city in the world, from small squares to large urban parks.

In many cultures, fountains continue to symbolize abundance, purity, and beauty, remaining central elements in many public squares and private gardens.

Fountains in Salento

Although fountains in Salento are not as numerous as in other Italian regions, they represent significant elements of the local cultural and artistic heritage, often tied to practical and symbolic functions.

In this context, Lecce is the subject of a saying of Bourbon origin, known as "The city without fountains," reflecting the irony and paradox associated with a place famous for its Baroque architecture and numerous decorative fountains, yet with scarce water resources. Despite the presence of many fountains, they were not always operational in the past, or lacked a sufficient water source to keep them running.

It is essential to mention the legendary Idume River, a watercourse that mostly flows underground, passing beneath the city of Lecce and surfacing only in a few specific points. Its source is near the town of Surbo, north of Lecce, and the river continues its course until it flows into the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the Idume provided drinking water and was used to irrigate fields. However, due to its underground nature and the karstic character of the territory, the river has always been difficult to manage and control. With the urban expansion of Lecce and environmental changes, much of its course has been covered, and today the Idume is mostly hidden beneath the city. Additionally, the presence of this underground river may be one of the main reasons behind the saying "Lecce, fountains without water." The city's fountains, although artistically rich, often had water supply problems due to the difficulty of accessing the water resources of the Idume River, hidden beneath the surface.

Historical sources attest that the oldest fountain in Lecce dates back to 1498, followed by another fountain at the end of the 16th century, located in the current Piazza Sant'Oronzo, between the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie and the Roman amphitheater. The structure consisted of a hemispherical stone basin supported by nymphs, with the city's civic emblem (a she-wolf walking and a holm oak tree crowned by five towers) rising in the center. Water spouted from the center of the oak, falling into the basin below and then into two concentric octagonal basins at the base, which rose slightly above the level of the square. The water supply was provided by a large well and a hydraulic machine with stone pipes, powered by animal force, which in 1678 also fed the new fountain by the renowned architect Giuseppe Zimbalo, which replaced the previous one. The new monument was dedicated to the reigning king, Charles II, represented by an equestrian statue, and remained active until 1841, when it was demolished. The pre-existing fountain was not destroyed but relocated to the park of the Orsini del Balzo Counts, where it remained until 1756.

Historical sources attest that the oldest fountain in Lecce dates back to 1498, followed by another fountain at the end of the 16th century, located in the current Piazza Sant'Oronzo, between the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie and the Roman amphitheater. The structure consisted of a hemispherical stone basin supported by nymphs, with the city's civic emblem (a she-wolf walking and a holm oak tree crowned by five towers) rising in the center. Water spouted from the center of the oak, falling into the basin below and then into two concentric octagonal basins at the base, which rose slightly above the level of the square. The water supply was provided by a large well and a hydraulic machine with stone pipes, powered by animal force, which in 1678 also fed the new fountain by the renowned architect Giuseppe Zimbalo, which replaced the previous one. The new monument was dedicated to the reigning king, Charles II, represented by an equestrian statue, and remained active until 1841, when it was demolished. The pre-existing fountain was not destroyed but relocated to the park of the Orsini del Balzo Counts, where it remained until 1756.

But was there water or not? There was and wasn't. Each time they wanted to make the fountain spout water, it was necessary to activate the well's hydraulic machine with a horse or donkey to fill the reservoir, so the fountain remained dry for most of the year, except on a few solemn occasions.

Today, the most representative fountain of Lecce is the Fountain of Harmony (also known as the Fountain of the Two Lovers), erected in 1927, on the occasion of the arrival of the aqueduct in the city, in front of the Castle of Charles V. This work, built in Trani stone, features two bronze statues placed on organ pipes of varying lengths: a man and a woman, both nude, holding up a shell from which they both drink. The sculptor intended to celebrate a very important moment for the city of Lecce through the allegory of love and sharing.

Moving away from the capital, we find other notable fountains in the province, which have become recognizable landmarks and points of reference for the communities where they are located.

The first one is in Nardò, and it is the "Fountain of the Bull", created in 1930. It bears the symbol of the city: a bull that makes water spout. Legend has it that the city was founded where a bull made water gush from the ground. The bull is also a symbol associated with the Spanish Aragonese, who ruled southern Italy for a period and arrived in Nardò during the Renaissance. This was a time when historical and literary attention was focused on the classical era, and the theme of myth, in which the bull has significance and frequency, was revived. Next to the fountain is a medallion featuring the city’s coat of arms and the phrase "Tauro non Bovi." The presence of the bull rather than the ox represents the strength of Aragonese rule or perhaps of the Neretine population itself.

The first one is in Nardò, and it is the "Fountain of the Bull", created in 1930. It bears the symbol of the city: a bull that makes water spout. Legend has it that the city was founded where a bull made water gush from the ground. The bull is also a symbol associated with the Spanish Aragonese, who ruled southern Italy for a period and arrived in Nardò during the Renaissance. This was a time when historical and literary attention was focused on the classical era, and the theme of myth, in which the bull has significance and frequency, was revived. Next to the fountain is a medallion featuring the city’s coat of arms and the phrase "Tauro non Bovi." The presence of the bull rather than the ox represents the strength of Aragonese rule or perhaps of the Neretine population itself.

In Gallipoli, between the historic center and the newer part of the city, stands the "Greek Fountain". Initially, local tradition and some critics believed that the fountain dated back to the 3rd century BC. However, further studies found it more accurate to place the architectural work in the Renaissance period. From 1548 until 1560, it stood near the now-lost Church of San Nicola. Then, in 1560, it was moved to its current location next to the Gallipoli Bridge.

BC. However, further studies found it more accurate to place the architectural work in the Renaissance period. From 1548 until 1560, it stood near the now-lost Church of San Nicola. Then, in 1560, it was moved to its current location next to the Gallipoli Bridge.

But the mystery of its origins persists: the style that created the fountain is that of Ancient Greek art, a culture that used myth as a form of expression. According to this theory, with the invasions of the Goths, the statues were removed and then reinserted into the structure in 1560. Whatever the true dating, the Greek Fountain still arouses great interest and curiosity today. The fountain consists of two facades, each about 5 meters high: one facing northwest and the other southeast.

The northwest facade serves as a support and dates back to 1765. On it stands the coat of arms of Gallipoli, featuring an image of a rooster with a crown and a Latin inscription that reads *fideliter excubat*, meaning "faithfully watches." Also prominently displayed are the insignia of King Charles III of Bourbon.

The northwest facade serves as a support and dates back to 1765. On it stands the coat of arms of Gallipoli, featuring an image of a rooster with a crown and a Latin inscription that reads *fideliter excubat*, meaning "faithfully watches." Also prominently displayed are the insignia of King Charles III of Bourbon.

Below is a watering trough where animals would drink, and in the 1950s, water was drawn from here for families without access to it at home.

The southeast facade is divided into three blocks, flanked by four caryatids that support the architrave, which is richly decorated and about 5 meters high. In the three sections between the four caryatids are bas-reliefs depicting the metamorphoses of three mythological figures: Dirce, Salmacis, and Byblis, women transformed into springs.

The most spectacular fountain is the "Monumental Cascade of Santa Maria di Leuca". Universally considered one of the most beautiful in Italy, this work, of high engineering value, has adorned the town for over 80 years. It forms the final stretch of one of Italy’s most ambitious and important projects, the Apulian Aqueduct, currently the largest in Europe. The cascade was created to celebrate the successful completion of the project and was inaugurated in 1939. In 1927, the Grand Siphon was finally completed, bringing water first to Lecce and then to the main towns of Salento, eventually reaching Santa Maria di Leuca. Between 1931 and 1941, the construction of the peripheral branches completed this grand project, which is now nestled in a stunning landscape of cliffs overlooking the sea and a pine forest. An imposing structure, it boasts a length of over 250 meters and a drop of about 120 meters, with a flow rate of 1,000 liters per second, ending directly in the sea. On both sides, two long staircases lead from the square of the overhanging Sanctuary of Finibus Terrae to the end of the cascade, where a Roman column has been placed, and then to the port. The cascade is not continuously on display to curious visitors, tourists, and spectators; instead, it is activated infrequently, especially during the summer, both to allow for the drainage and discharge of water and to create a suggestive and fascinating spectacle.

The most spectacular fountain is the "Monumental Cascade of Santa Maria di Leuca". Universally considered one of the most beautiful in Italy, this work, of high engineering value, has adorned the town for over 80 years. It forms the final stretch of one of Italy’s most ambitious and important projects, the Apulian Aqueduct, currently the largest in Europe. The cascade was created to celebrate the successful completion of the project and was inaugurated in 1939. In 1927, the Grand Siphon was finally completed, bringing water first to Lecce and then to the main towns of Salento, eventually reaching Santa Maria di Leuca. Between 1931 and 1941, the construction of the peripheral branches completed this grand project, which is now nestled in a stunning landscape of cliffs overlooking the sea and a pine forest. An imposing structure, it boasts a length of over 250 meters and a drop of about 120 meters, with a flow rate of 1,000 liters per second, ending directly in the sea. On both sides, two long staircases lead from the square of the overhanging Sanctuary of Finibus Terrae to the end of the cascade, where a Roman column has been placed, and then to the port. The cascade is not continuously on display to curious visitors, tourists, and spectators; instead, it is activated infrequently, especially during the summer, both to allow for the drainage and discharge of water and to create a suggestive and fascinating spectacle.

Lastly, but no less important, are the "Apulian Aqueduct fountains". Every town in Salento has at least one. These are small public fountains, all identical (128 cm high, 38 cm circular base, conical shape, topped with a cap and a small basin for water recovery, entirely made of cast iron, intermittent jet tap with an internal brass mechanism, still handcrafted today). They represent the symbol of the Apulian Aqueduct, the historic little fountain familiar to many squares in Puglia and southern Italy, which, starting in 1914, brought the first clean public water to Puglia, and still today, it stands as the undisputed icon of this epochal social achievement. Over the years, stories and rhymed poems about the fountain have multiplied, creating a popular literature, often in dialect: "All’acqua, all’acqua, alla fendana nova, ci non tene la zita se la trova" (“To the water, to the water, to the new fountain, whoever doesn't have a fiancée will find one”), says an anonymous nursery rhyme from the 1920s, reflecting the unconditional affection that the people of Puglia have for this simple life-giving tool.

Lastly, but no less important, are the "Apulian Aqueduct fountains". Every town in Salento has at least one. These are small public fountains, all identical (128 cm high, 38 cm circular base, conical shape, topped with a cap and a small basin for water recovery, entirely made of cast iron, intermittent jet tap with an internal brass mechanism, still handcrafted today). They represent the symbol of the Apulian Aqueduct, the historic little fountain familiar to many squares in Puglia and southern Italy, which, starting in 1914, brought the first clean public water to Puglia, and still today, it stands as the undisputed icon of this epochal social achievement. Over the years, stories and rhymed poems about the fountain have multiplied, creating a popular literature, often in dialect: "All’acqua, all’acqua, alla fendana nova, ci non tene la zita se la trova" (“To the water, to the water, to the new fountain, whoever doesn't have a fiancée will find one”), says an anonymous nursery rhyme from the 1920s, reflecting the unconditional affection that the people of Puglia have for this simple life-giving tool.

Fountains in Salento, though not as numerous as in other Italian regions, are still an integral part of the urban and rural landscape. Besides providing water, these fountains served and still serve as meeting places, venues for festivities and socialization, representing symbols of life and community. For tourists, the fountains offer an opportunity to immerse themselves in local history and appreciate the architectural beauty of the region.

Salento, with its combination of historical and modern elements, continues to value fountains as part of its cultural heritage, reflecting the region's rich artistic tradition and the vitality of its people.

Between clay and dreams: salentine ceramics, ancient roots and architectural visions

Salentine ceramics, one of the most authentic and ancient expressions of Apulian craftsmanship, represent a cultural heritage of inestimable value. This artisanal tradition, born centuries ago, has evolved over the ages in forms, styles, and uses, while always maintaining a deep connection with the local territory and architecture.

The word "ceramics" itself has Greek origins, from "kéramos," which means "potter's clay." Due to its great versatility, this material has been used over the centuries to produce various objects, crafted by the skilled hands of expert artisans and ready to be decorated with a variety of techniques.

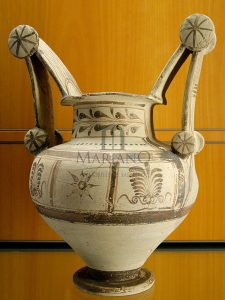

The origins of Salentine ceramics date back to prehistoric times when local populations began shaping clay to create everyday utensils and ritual objects. Among the most celebrated traditional pottery for its beauty, the Messapian production, typical of Salento between the eighth and third centuries BC, holds a place of honor. The Messapians, an ancient population of Illyrian origin, created vases (notably ollas and trozzelle) with increasingly complex decorations, starting with geometric motifs in the early period and later influenced by Greek patterns. Soon, Messapian vases began to be fully decorated, including floral and figurative motifs, before returning to geometric and monochromatic decorations in the third period, this time with clear Hellenic influences. New forms of vases also emerged, such as the pyxis or the krater, but the typical trozzella, with its ovoid body and ribbon-like handles equipped with four characteristic wheels, remained the truest and purest expression of Messapian art, along with types like the pignata, used for cooking typical Salentine dishes, and the capase, for storing water.

The origins of Salentine ceramics date back to prehistoric times when local populations began shaping clay to create everyday utensils and ritual objects. Among the most celebrated traditional pottery for its beauty, the Messapian production, typical of Salento between the eighth and third centuries BC, holds a place of honor. The Messapians, an ancient population of Illyrian origin, created vases (notably ollas and trozzelle) with increasingly complex decorations, starting with geometric motifs in the early period and later influenced by Greek patterns. Soon, Messapian vases began to be fully decorated, including floral and figurative motifs, before returning to geometric and monochromatic decorations in the third period, this time with clear Hellenic influences. New forms of vases also emerged, such as the pyxis or the krater, but the typical trozzella, with its ovoid body and ribbon-like handles equipped with four characteristic wheels, remained the truest and purest expression of Messapian art, along with types like the pignata, used for cooking typical Salentine dishes, and the capase, for storing water.

During the Greco-Roman period, ceramic production in the Salento region was enriched with more sophisticated techniques and decorations, influenced by contacts with Mediterranean civilizations. These cultural exchanges contributed to the development of a ceramic tradition characterized by a great variety of forms and decorative motifs.

With the advent of the Middle Ages and then the Renaissance, Salentine ceramics continued to thrive, establishing themselves as a refined art. Artisan workshops multiplied in the main cities of Salento, such as Lecce, Grottaglie, and Cutrofiano, where artisans experimented with new glazes and decorative techniques. During the Baroque period, Salentine ceramics reached the pinnacle of their artistic expression, thanks to the richness of floral motifs and mythological figures.

workshops multiplied in the main cities of Salento, such as Lecce, Grottaglie, and Cutrofiano, where artisans experimented with new glazes and decorative techniques. During the Baroque period, Salentine ceramics reached the pinnacle of their artistic expression, thanks to the richness of floral motifs and mythological figures.

Over the centuries, Salentine ceramics have undergone continuous evolution, adapting to new aesthetic and functional needs. Production has expanded from creating everyday objects, such as plates, vases, and pots, to producing decorative elements for architecture, such as majolica tiles and rosettes. The blending of other Italian and European ceramic traditions has enriched the Salentine stylistic repertoire, leading to the creation of unique pieces that combine tradition and innovation.

Today, Salentine ceramics keep traditional artisanal techniques alive while also embracing new technologies and contemporary design trends. Many artisan workshops, often family-run, continue to produce ceramics using ancient methods but with an eye on modern market demands.

In contemporary usage, Salentine ceramics are applied in various contexts, both as functional and decorative elements. Ceramic objects are appreciated for their beauty and their ability to tell the story and culture of Salento. In addition to traditional kitchen items, Salentine ceramics are used to create furniture accessories, such as lamps, tables, and tiles, adding a touch of elegance and authenticity to spaces.

Ceramic craftsmanship is also an important economic sector for the region, attracting cultural tourism. Fairs and markets dedicated to Salentine ceramics draw visitors from all over the world, eager to discover and purchase unique, handmade pieces.

Among the most characteristic elements are:

The Pumo

The name and the reasons for the production of the pumo, which has become one of the most distinctive symbols of the artisanal tradition, can be traced back to the history of ancient Rome when the cult of Pomona, the goddess of fruits, was celebrated. The word pumo derives from the Latin "pomum," meaning "fruit."

The name and the reasons for the production of the pumo, which has become one of the most distinctive symbols of the artisanal tradition, can be traced back to the history of ancient Rome when the cult of Pomona, the goddess of fruits, was celebrated. The word pumo derives from the Latin "pomum," meaning "fruit."

Its shape recalls a bud enclosed by four acanthus leaves, symbolizing life being renewed. It is a symbol of prosperity and fertility, but also of chastity, immortality, and resurrection. Additionally, it has an apotropaic function, acting as a sort of amulet capable of warding off evil and bad luck. For these reasons, this artifact initially spread among the noble families of Puglia, who used it as a decorative element on the facades of noble mansions and on wrought iron railings, before becoming popular among the rest of the population, including peasants.

and fertility, but also of chastity, immortality, and resurrection. Additionally, it has an apotropaic function, acting as a sort of amulet capable of warding off evil and bad luck. For these reasons, this artifact initially spread among the noble families of Puglia, who used it as a decorative element on the facades of noble mansions and on wrought iron railings, before becoming popular among the rest of the population, including peasants.

The pumi of the nobility were distinguished from those of others. In fact, the lords of the town would personalize them with heraldic symbols and a varying number of leaves around the bud, as a testament to the notoriety, authority, and wealth of their family. The function of the pumo is not to chase away bad luck or evil; it precedes bad luck and keeps it at bay, acting as an impenetrable barrier to evil. The pumo is therefore a good luck charm, which, according to tradition, should not be purchased but gifted or received as a gift.

Capase or Capasoni

The farmers of Puglia and Salento used these beautiful terracotta containers for various purposes, mainly to store liquids like extra virgin olive oil, water, or wine. The value of these containers was that they could preserve the characteristics of the contained liquid, particularly its temperature. The name capasa comes from the Latin "capax capacis," meaning "capable," referring to the often large capacity of these containers and their usefulness in storing liquids. The capasa is also known as capasone, with an augmentative meaning. In past centuries, the larger capase were used instead of barrels during the grape harvest. Just a few dozen of the largest ones (with a capacity of at least 200 liters) were enough to store wine. Usually, the mouth of the capasoni was sealed with a plug made of lime and ash. Near the base of the capasone, about twenty centimeters from the bottom, there was a drainage spout to which a sort of tap was attached, called "cannedda." Sometimes, a small cork plug, known as "pipulu," was used instead. This made it easy to obtain the right amount of wine or oil by bringing a container close to the cannedda.

The farmers of Puglia and Salento used these beautiful terracotta containers for various purposes, mainly to store liquids like extra virgin olive oil, water, or wine. The value of these containers was that they could preserve the characteristics of the contained liquid, particularly its temperature. The name capasa comes from the Latin "capax capacis," meaning "capable," referring to the often large capacity of these containers and their usefulness in storing liquids. The capasa is also known as capasone, with an augmentative meaning. In past centuries, the larger capase were used instead of barrels during the grape harvest. Just a few dozen of the largest ones (with a capacity of at least 200 liters) were enough to store wine. Usually, the mouth of the capasoni was sealed with a plug made of lime and ash. Near the base of the capasone, about twenty centimeters from the bottom, there was a drainage spout to which a sort of tap was attached, called "cannedda." Sometimes, a small cork plug, known as "pipulu," was used instead. This made it easy to obtain the right amount of wine or oil by bringing a container close to the cannedda.

Capasoni were not only used for agricultural work but also for transporting liquids back and forth across the Mediterranean. They were key players in trade for a long time, even to the Middle and Far East.

Today, capase and capasoni have come back into fashion, and there is a large market revolving around the search for old specimens and their revaluation. It is common to see them at the entrances of prestigious tourist resorts, in the courtyards of many noble villas, and in gardens and outdoor areas.

The Rooster

The undisputed protagonist of the decoration of Apulian ceramics, the rooster can be found on many everyday objects, most of which are used at the table during meals. Its history has ancient and extraordinary origins, and the rooster symbolizes the figure of Mercury, the god of commerce, profit, and eloquence. The rooster is therefore identified as a sacred animal, which, besides representing Mercury, can be linked to other important symbols. It is considered almost a domestic animal, capable of driving away all negative energies and malice from one's home. Lastly, but not least importantly, the famous Apulian rooster is considered a symbol of fertility.

The bond between Salentine ceramics and architecture is particularly strong.

Since the Baroque period, majolica tiles and decorative ceramic panels have been used to embellish churches, palaces, and noble residences. Ceramics became a distinctive element of Lecce Baroque, with its vibrant colors and ornamental motifs enriching the facades of buildings.

Even in contemporary architecture, Salentine ceramics continue to play an important role. Architects and designers often choose ceramic materials for their aesthetic and functional qualities, such as durability and ease of maintenance. Ceramic tiles are used both indoors and outdoors, creating continuity between tradition and new trends in sustainable architecture.

Salentine ceramics, with their ancient roots and continuous evolution, represent a symbol of the culture and identity of Salento. Their relationship with architecture and their current use testify to the ability of this tradition to renew and adapt to the times while preserving its authenticity. The future of Salentine ceramics looks bright, with new generations of artisans ready to carry on this heritage with passion and creativity.

Apotropaic Architecture in Salento: Symbols and Secrets of a Millenary Tradition

Apotropaic architecture in Salento represents a fascinating and meaningful tradition, which intertwines symbolism, religiosity and popular culture. This type of architecture, characterized by elements designed to protect homes and places of worship from evil influences, finds its roots in ancient practices and has developed over the centuries, adapting to the cultural and social changes of the region.

The term “apotropaic” derives from the Greek “apotrépein”, which means “to drive away”, and refers to objects, symbols or architecture designed to drive away or keep away evil. In Salento, as in many other regions of the Mediterranean, these practices are deeply rooted in the local culture and have their origins in antiquity.

The influences of the apotropaic architecture of Salento are to be found in the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, which had already developed a series of rituals and symbols to protect their homes from evil spirits. Over time, these practices have merged with local religious and popular beliefs, giving rise to a unique architectural tradition.

During the Middle Ages, the apotropaic architecture of Salento took on a more defined connotation, with the introduction of decorative and structural elements specifically designed for protection from the forces of evil.

The main elements of apotropaic architecture are many:

- Mascarons and Stone Heads, or grotesque masks or faces carved in stone, often placed above doors or on the corners of buildings. It was believed that these frightening images could ward off evil spirits or the “evil eye”, or the bad

omen resulting from a malevolent look. One of the most characteristic examples is the “Loggia degli Sberleffi”, located in Giuliano di Lecce, built in 1609 on 15 corbels representing different figures that mock, precisely, the evil spirits that would like to disturb the domestic peace, thus driving them away with their grimaces, tongues and long faces. Some of the figures have an appearance that borders on the grotesque, elf ears, drooping cheeks, enormous moustaches. Others are extremely nice. They certainly represent different moments in a man's life, from faces that range from youth to old age, an aspect also highlighted by the camouflage and facial features.

omen resulting from a malevolent look. One of the most characteristic examples is the “Loggia degli Sberleffi”, located in Giuliano di Lecce, built in 1609 on 15 corbels representing different figures that mock, precisely, the evil spirits that would like to disturb the domestic peace, thus driving them away with their grimaces, tongues and long faces. Some of the figures have an appearance that borders on the grotesque, elf ears, drooping cheeks, enormous moustaches. Others are extremely nice. They certainly represent different moments in a man's life, from faces that range from youth to old age, an aspect also highlighted by the camouflage and facial features.

- Fairies, beautiful and graceful sculptures, which instead have their origins in the oral tradition of the fable, also placed outside the buildings for protective purposes. The most evident

testimony is present in the outskirts of Lecce, at the Masseria Tagliatelle, a sixteenth-century noble residence, which contains within it the "Ninfeo delle Fate" a place of water and idleness, in which the ladies gathered to stay cool and spend time together. Without a doubt a magical place, with all its load of centuries-old charm. It is called this way for the sculptures that dominate the twelve niches, six on each side. Six remain: three on each wall. Six life-size female figures that seem to have been drawn by Botticelli. The statues of these mythological creatures, one with its head crowned with flowers, welcome passers-by towards the area where the spring water penetrated and the noble women chatted about this and that.

testimony is present in the outskirts of Lecce, at the Masseria Tagliatelle, a sixteenth-century noble residence, which contains within it the "Ninfeo delle Fate" a place of water and idleness, in which the ladies gathered to stay cool and spend time together. Without a doubt a magical place, with all its load of centuries-old charm. It is called this way for the sculptures that dominate the twelve niches, six on each side. Six remain: three on each wall. Six life-size female figures that seem to have been drawn by Botticelli. The statues of these mythological creatures, one with its head crowned with flowers, welcome passers-by towards the area where the spring water penetrated and the noble women chatted about this and that.

- Pinnacles and “Pumi”, where the first are cone- or pyramid-shaped decorations often found on the roofs of houses (especially in Masserie), and the second, the “pumi”, are small ornamental spheres typical of the Salento tradition. They represent a rosebud that is about to bloom, as if to demonstrate the elegance of nature, and this is why in addition to being an original furnishing object, it has a very important meaning, in fact it symbolizes: luck, abundance, prosperity, fertility and novelty.

- Crosses and Religious Symbols, carved or painted on the walls, above the doors, or integrated into the facade decorations. The Coastal Towers are a singular case, on which we find symbolic decorations, such as the Maltese cross or other engravings, intended to protect the inhabitants and discourage attacks by Saracen pirates. A sign of the Christian faith, they served as divine protection against evil. They were often placed in strategic points of the buildings to strengthen their apotropaic function.

- Rose windows, or circular stone windows, often decorated with geometric or floral motifs, typical of Romanesque and Gothic churches, which in addition to having an aesthetic and practical function for internal lighting, symbolically represent the sun or the divine eye, protecting the building from negative energies.

- Sculpted frames, friezes and geometric motifs are often present around doors and windows. These elements not only embellish the structure, but were also intended as symbolic barriers against evil spirits, which were believed to be confused or blocked by complex patterns.

- Altars and niches containing sacred images or statues of saints, frequently placed inside homes or on external walls, offer spiritual protection and act as a point of prayer for the family, invoking divine blessing and protection upon the home.

Apotropaic architecture in Salento mainly uses local stone, Lecce stone, which is easy to work with but resistant, to create these decorative elements. In some cases, materials such as wrought iron are also used, especially for crosses and other symbols placed on roofs or on the sides of doors.

Apotropaic architecture in Salento mainly uses local stone, Lecce stone, which is easy to work with but resistant, to create these decorative elements. In some cases, materials such as wrought iron are also used, especially for crosses and other symbols placed on roofs or on the sides of doors.

Despite the passage of time and the advent of modernity, apotropaic architecture in Salento still retains a particular charm and a deep meaning for the inhabitants of the region. Many of the ancient practices and symbols have been passed down from generation to generation and continue to be present in many homes and places of worship.

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in these traditions, thanks also to archaeological and anthropological studies that have rediscovered the historical and cultural value of these architectural elements. Cultural tourism has helped bring these testimonies of the past to light, which are appreciated not only for their aesthetic value, but also for their symbolic meaning.

Apotropaic architecture in Salento, in addition to having a protective function, represents a way to express one's cultural and religious identity. Apotropaic symbols and decorations reflect a vision of the world in which the sacred and the profane are intertwined, and where divine protection is sought through the creation of a safe and sacred space.

Furthermore, these architectural elements testify to the resilience of the Salento culture, which has been able to adapt to changes without losing its connection with its roots. Apotropaic architecture continues to be a distinctive element of the urban and rural landscape of Salento, helping to keep alive a thousand-year-old tradition.

Apotropaic architecture in Salento represents a cultural heritage of inestimable value, which allows us to better understand the beliefs and practices of a society deeply rooted in its history and tradition. Through the analysis and conservation of these architectural elements, it is possible not only to preserve a piece of local history, but also to reflect on the complex relationship between man, architecture and spirituality.

The Stones Tell: The Dry Stone Walls of Salento, History and Resilience in the Landscape

Dry stone walls, characteristic of the Salento landscape, represent a tradition that has its roots in ancient times. These structures, built without the use of mortar, are an extraordinary example of rural architecture, a symbol of a past rich in history and culture. In this article we will explore the origins, evolution and current use of dry stone walls in Salento.

The first evidence of dry stone walls in Salento dates back to pre-Roman times, and the walls of this period have a structure of square blocks placed horizontally.

The local populations, the Messapians, began to use them to protect their crops from grazing, to mark the border between one property and another, as a small enclosure for animals (ncurtaturi), or they built them along the coast to protect crops from atmospheric agents.

The construction techniques were handed down from generation to generation, improving and adapting over time, and a real "craft" was born, handed down from father to son, the so-called "paritaru" ("parite" in Salento dialect means wall).

Currently the most significant evidence of these ancient walls is found in northern Salento, in the "Archaeological Park of the Messapian Walls", which extends for 150,000 m² to the north-east of the municipality of Manduria. Inside, large sections of the triple circle of walls that surrounded the city in the Messapian era are preserved.

During the Roman period, the practice of building dry stone walls became more widespread. Following the example of the civilizations that preceded them, the Romans adopted more than one dry stone construction technique (opus, in Latin), but the most widespread in Salento is the polygonal work (opus siliceum). The construction technique involves the composition of a rock bank arranged in two parallel rows of large stones, then two more rows of smaller stones converging upwards are added and the empty spaces are filled with other thinner material. The rows are then tied together with other larger stone slabs, this time inserted edgewise. In this case too, the spaces are filled with material. To finish everything off, the remaining cracks in the facades are closed by inserting stone chips. The Romans, expert engineers, recognized the effectiveness of these structures in containing the land and in delimiting agricultural areas.

In the Middle Ages, dry stone walls continued to be used mainly for the creation of terraces on hilly terrain, to prevent soil erosion and facilitate cultivation, and also to build rainwater channeling systems, improving the irrigation of fields. These structures were also very useful in animal breeding, and the projecting walls, in addition to enclosing their courtyards, were insurmountable by wolves, foxes and cattle herders, as well as ensuring the possibility of saving on labor for the care of animals, raising them in a semi-wild state.

During the Renaissance, a period of great expansion and innovation in many sectors, agriculture also underwent significant changes. This era, characterized by the rediscovery of antiquity and a growing interest in science and technology, profoundly influenced the way in which agricultural landscapes were managed and structured. In Salento, dry stone walls became even more widespread and vital to the agricultural economy, responding to new production and environmental needs. With the expansion of agriculture and the increase in production needs, these structures proved essential not only for the delimitation of land and the control of soil erosion, but also for harmonious integration into the rural landscape.

The twentieth century saw a partial abandonment of dry stone walls, due to the mechanization of agriculture and increasing urbanization. With the introduction of modern agricultural machinery, the way in which the land was cultivated changed radically, as heavy machinery required large and obstacle-free spaces to function effectively, and therefore many dry stone walls were knocked down or destroyed. This change also led to a loss of traditional cultivation techniques and the knowledge associated with the construction and maintenance of dry stone walls.

The increasing urban development and the expansion of residential and industrial areas also significantly affected the landscape of Salento, because with urban expansion rural areas were often converted into urban or residential areas, leading to the demolition of dry stone walls to make room for new buildings. Furthermore, many dry stone walls remained abandoned and in a state of decay, as rural communities moved to cities and peri-urban areas.

In the last decades of the twentieth century there was a change of trend, and there was a growing recognition of the cultural and landscape importance of dry stone walls. Historians, archaeologists and environmentalists began to highlight their historical and cultural value as an integral part of the rural heritage of Salento. Furthermore, people began to understand how much dry stone walls contribute to the beauty and uniqueness of the Salento landscape, offering a distinctive element that enriches the view and understanding of the territory.

All this has led, nowadays, to a renewed interest in their conservation, with significant consequences. Today, in fact, the dry stone walls of Salento are recognized as a cultural heritage of great value. In 2018, the art of dry stone walls was inscribed on the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage, a recognition that has given new life to conservation and restoration efforts. Traditional techniques are now taught to new generations, ensuring the continuity of this ancient art.

Furthermore, dry stone walls are increasingly appreciated for their positive environmental impact. In addition to preventing soil erosion, they promote biodiversity, offering refuge to numerous species of flora and fauna, a true "ecological corridor" that allows the transmission of a microfauna rich in insects, reptiles and amphibians that operate spontaneously, in synergy with human agriculture, to maintain a healthy and parasite-free environment. The interstices become their home and hiding place. The dry stone walls, with the spontaneous vegetation that grows between the stones or close to the walls themselves, constitute an important ecosystem. In their correspondence a particular microclimate is created, favorable to Mediterranean plants that can thus, thanks to the greater availability of water, overcome the summer crisis.