Chianche Salentine: Architectural Heritage and Village Identity

In Salento, not everything cultural is written in books or stored in museums. One of the region’s deepest, oldest and most vibrant heritages is carved into the land itself: the chianche.

These are not simple stone slabs. They are memory, identity, and a geological script millions of years old that has shaped both the urban and rural landscapes of Salento.

Origins and History

Origins and History

Chianche are limestone slabs extracted since ancient times from local quarries. Their use is very ancient: traces can be found as far back as the Messapian period and later during the Roman era, when they began to be used not only for paving but also to define spaces and build residential structures.

Salento, a land historically poor in wood and easily worked materials, found great value in its stone. Here, stone is not just a material—it is a strategic resource that has shaped architecture and the very way of living.

Legends and Symbolism

Many local tales connect chianche with the idea of protection.

People believed that a well-placed stone at a home’s threshold could ward off negativity and the evil eye.

And that those who built with local stone would always have stability and grounding, because “a house made from this land will never betray you.”

Even today, in abandoned masserie or ancient pajare, the surviving stone slabs seem to confirm these beliefs.

Uses in the Past

-

paving of courtyards, streets, neighborhood squares and piazzas

-

dry-stone roofing of pajare and rural trulli

-

external staircases and entrances of masserie

-

protective elements for wells, underground oil mills and water channels

They were eco-friendly materials avant la lettre, sourced locally, worked by hand and laid without chemical adhesives.

Contemporary Use

Contemporary Use

Today chianche are considered a symbol of authenticity and value, widely used in the restoration of historic buildings and in the design of contemporary Mediterranean-style spaces.

They are commonly used for:

-

farmhouse and luxury masseria renovations

-

pavements in B&Bs, historical residences, boutique hotels and vacation homes

-

modern interiors seeking a minimal Mediterranean aesthetic

-

slow-hospitality structures

-

paving the streets of historic town centers, preserving the original atmosphere and architectural identity of Salento’s villages

They are regarded as a sustainable material: durable, natural and impossible to replicate industrially.

Architecture and Identity

Salento’s architecture cannot exist without its stone.

The chianca is the material that shaped an entire aesthetic: essential, clean, resilient, tied to sunlight and to the bright tones that reflect the sea.

Where there is chianca, there is recognizability—an identifying element linking past, present and future.

The Future of Chianche

The Future of Chianche

The key issue for the years to come is protection.

Excessive exportation in recent decades has depleted certain areas and increased local costs. A more conscious management approach is needed:

-

valorizing abandoned historic quarries through cultural routes

-

supporting local artisans in traditional stone-working techniques

-

prioritizing restoration rather than industrial replacement

-

creating territorial certification and traceability labels

Chianche can become not only aesthetic elements but also cultural and educational assets.

They have the potential to become part of exhibitions, open-air museums, architectural itineraries, and heritage tourism routes.

The future can be virtuous if chianche are recognized for what they truly are: an irreplaceable heritage, a stone that speaks.

And through them, Salento will continue to tell its story for centuries.

Urbex in Salento: Journey Through Forgotten Treasures and Hidden Memories

Among ancient masserie (fortified farmhouses), elegant villas, and villages frozen in time, there lies a silent world that speaks of history, memories, and social change. This world is that of urbex, or urban exploration — a practice that combines adventure, photography, historical research, and a deep respect for forgotten cultural heritage.

The allure of urbex comes from the contrast between decay and beauty: deserted buildings that tell the stories of those who once lived there, silent witnesses of distant eras, and traces left untouched by time.

In Salento, a land rich in historical layers, urbex takes on a unique meaning, becoming not only an aesthetic discovery but also a reflection on the present and the future.

What Urbex Is and How It Started

The word urbex comes from the English term urban exploration. It refers to the practice of exploring abandoned or otherwise inaccessible places: disused factories, old hospitals, deconsecrated churches, ruined historic villas, industrial buildings, forgotten theaters, and even entire villages.

The word urbex comes from the English term urban exploration. It refers to the practice of exploring abandoned or otherwise inaccessible places: disused factories, old hospitals, deconsecrated churches, ruined historic villas, industrial buildings, forgotten theaters, and even entire villages.

It’s not just about adventure — urbex is also a form of research and documentation.

Urbexers — as enthusiasts are called — take photographs, shoot videos, and tell stories, bringing fragments of collective memory back to light.

At the heart of urbex lies a fundamental rule: absolute respect for the location.

Nothing is taken, nothing is damaged, and nothing is left behind. The goal is to observe and bear witness, not to alter.

Urbex has deep roots: as early as the 19th century, there were individuals exploring hidden urban spaces, though the modern definition emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. With the rise of the internet and social media, urbex has spread globally.

Platforms like Instagram, YouTube, and specialized blogs have turned these explorations into visual storytelling, fostering communities of enthusiasts worldwide.

Urbex in Italy

Italy, with its vast historical and architectural heritage, offers countless opportunities for exploration.

Crumbling noble villas, former industrial complexes, abandoned psychiatric hospitals, monasteries, castles, and even entire ghost towns — every region hides spaces suspended between past and present.

In Italy, urbex carries a unique layer of meaning. It’s not only about discovering forgotten places but also about reflecting on social and economic transformations.

Many urbex sites in Italy tell stories of emigration, changes in local industries, properties left without heirs, or public buildings abandoned due to economic crises or political decisions.

Urbex in Salento: Between Masserie, Noble Villas, and Ghost Villages

Salento, a land of crossroads and cultural exchanges, is a true paradise for urbex enthusiasts.

Salento, a land of crossroads and cultural exchanges, is a true paradise for urbex enthusiasts.

Here, abandonment takes on distinctive forms, often linked to rural history and the aristocratic life of the countryside.

Some of the most common types of locations encountered during explorations include:

-

Fortified Masserie: ancient agricultural complexes, often built with defensive features, dating back as far as the 16th to 18th centuries. Many have been restored and transformed into tourist facilities, while others remain silent and untouched, with watchtowers and courtyards now overtaken by vegetation.

-

Noble Villas: the former summer residences of local aristocratic families, richly decorated and featuring gardens, private chapels, mosaic floors, and frescoes. Their abandonment creates hauntingly beautiful scenes, where art and decay coexist.

-

Ghost Villages: small towns that lost their populations due to emigration or economic shifts, now left deserted and frozen in time.

-

Deconsecrated Religious Buildings: private chapels, convents, and rural churches that are no longer in use, often still containing altars and original decorations.

Urbex Salento: Telling the Stories of Forgotten Places

One of the most intriguing projects dedicated to urban exploration in the region is Urbex Salento, created in 2021 by Daniela Stabile, a passionate photographer and history enthusiast.

One of the most intriguing projects dedicated to urban exploration in the region is Urbex Salento, created in 2021 by Daniela Stabile, a passionate photographer and history enthusiast.

Her Instagram page serves as a visual diary where each photograph not only documents abandoned sites but also tells their stories, restoring dignity to what remains.

Daniela’s work goes beyond capturing evocative images. It is also a form of social commentary.

Each photographed place becomes an invitation to reflect on abandonment, degradation, and the urgent need for preservation and restoration.

As she explained in an interview with QuiSalento, for her, urbex is a way to preserve collective memory, giving a voice to places that might otherwise be lost to time.

Iconic Urbex Locations in Salento

Without revealing exact locations — to honor the urbex community’s code of protecting sites — here are some common types of places often explored in Salento:

-

Old factories and tobacco warehouses: remnants of a once-thriving local industry, especially in the inland areas between Lecce and Maglie.

-

Noble villas along the Ionian and Adriatic coasts, built mostly between the 19th and early 20th centuries, featuring grand staircases, panoramic terraces, and rooms adorned with frescoes.

-

Fortified masserie in the Capo di Leuca area, particularly around Presicce, Ugento, and Patù, where you can still find traces of stables, underground olive oil mills (frantoi ipogei), and subterranean granaries.

-

Semi-abandoned villages, where a few houses are still inhabited while others stand empty, with doors ajar and furniture left untouched.

-

Private chapels hidden in the countryside, decorated with faded frescoes and altars carved from local pietra leccese limestone.

These locations hold immense historical and emotional value.

Exploring them becomes a journey through time, unveiling the rural life, aristocratic heritage, and social changes that have shaped the region.

Urbex as a Cultural Resource

Urbex is more than just a personal passion — in Salento, it has the potential to become a cultural and tourism resource.

Urbex is more than just a personal passion — in Salento, it has the potential to become a cultural and tourism resource.

When managed responsibly and respectfully, it could give rise to sustainable tourism experiences that blend history, art, architecture, and storytelling. Some possibilities include:

-

Photography exhibitions dedicated to abandoned places, like those already held in some Salento towns.

-

Cultural events and guided itineraries that narrate the history of restored sites, transforming them into vibrant spaces for communities and visitors.

-

Urban regeneration projects, where forgotten buildings are reborn as cultural centers, museums, boutique accommodations, or community hubs.

Conclusion

Urbex encourages us to look beyond appearances, to discover the hidden beauty of abandoned places.

In Salento, this practice carries a special significance: it tells the story of a land rich in history, highlights the fragility of its cultural heritage, and sparks reflection on memory and collective identity.

Exploring, photographing, and sharing these places means preserving their memory — and perhaps laying the foundation for a future where abandonment can turn into revival.

In every broken window and every faded fresco lies a story worth listening to and sharing.

Collane di peperoncino - Tropea - Calabria

Salento is not only a land of sea and Baroque: it is also a land of intense flavors, Mediterranean scents, and symbols that tell stories of identity and belonging. Among these, the chili pepper – the maru in Salentino dialect – holds a special place, tied to popular culture, architecture, and even legends passed down through generations.

Origins and History of Chili Peppers in Salento

Origins and History of Chili Peppers in Salento

Chili peppers arrived in Europe after the discovery of the Americas, but in Salento they quickly found fertile ground. Grown in rural gardens and in the courtyards of traditional houses, they soon became a key ingredient in peasant cuisine: poor in resources, but rich in flavor.

Not only a condiment: for a long time, the chili pepper was also considered a “natural amulet”, a symbol of protection against the evil eye. In many Salento homes, it was hung on doors or windows, often in strings resembling coral necklaces.

Symbols and Legends

The elongated shape and bright red color made the chili pepper a powerful sign of fertility and vital energy. Folk beliefs held that carrying one in your pocket or hanging a small bunch in the kitchen would keep misfortune away.

In some towns of Salento, chili peppers were even intertwined with garlic and hung under the arches of farmhouses or near wells, as a symbol of protection over food reserves and harvests.

Architecture and the Culture of Chili Peppers

In Salento, chili peppers are not just an ingredient or an amulet: they are part of the architectural scenery of the towns.

-

Whitewashed walls and red strings: in courtyard houses and farmsteads, chili peppers were strung in long braids (nzerti) and left to dry on lime-washed walls. This color contrast – the bright white of the stone and the fiery red of the chili peppers – became almost a hallmark of Salento’s urban landscape.

-

Courtyards and balconies: in historic houses with loggias or balconies made of Lecce stone, chili peppers were hung like natural ornaments. Sometimes, together with garlic wreaths or olive branches, they formed decorations blending usefulness, protection, and beauty.

-

Apotropaic elements: in fortified farmhouses, next to votive niches dedicated to saints or Madonnas, strings of chili peppers could be found hanging on the doors of stables or granaries. They were not only a way to repel insects but also symbolic protection against the evil eye and envy.

The presence of chili peppers in domestic and rural architecture is an identity marker that reveals the fusion of practical function and symbolic meaning.

Legends and Ancient Stories About Chili Peppers in Salento

Legends and Ancient Stories About Chili Peppers in Salento

Chili peppers are linked to many folk beliefs which, although common in Southern Italy, took on unique nuances in Salento:

-

Chili peppers against the “jettatura” (evil eye)

In Lecce during the 19th century, market vendors always carried a dried chili pepper in their pockets. It was a defense against the jettatura, especially when handling money or closing deals. Even today, many elders keep a bunch of chili peppers near their wallets or hanging in the kitchen. -

The wedding ritual

In some villages of the Capo di Leuca, there was a custom of giving newlyweds a string of chili peppers to hang at the entrance of their new home. A symbol of fertility and passion, it was believed to protect the couple and bring prosperity. -

The legend of the farmer from Ruffano

A popular tale tells of a farmer from Ruffano who, tired of thefts in his fields, planted rows of chili peppers around his vegetable garden. It is said that thieves, frightened by the fiery burn of the fruit and convinced it had magical powers, stopped coming. Since then, in the town, the chili pepper has been considered a symbol of protection and abundance. -

Chili peppers and fishermen

Along the coast, fishermen used to hang bunches of chili peppers on their boats or nets to protect themselves from storms and bring good fortune. Some seafaring tales say that during full moon nights, the red reflections of the hanging chili peppers shone like enchanted lights, a symbolic guide for their safe return home.

A Heritage to Live (Even by Living in It)

The chili pepper, with its energy and vitality, is the perfect metaphor for Salento: authentic, strong, unmistakable.

Those who choose to buy a home here do not just acquire a property, but become part of a living culture, made of flavors, legends, and community festivals. Imagine living in an old courtyard house, hanging strings of chili peppers glowing red against whitewashed walls: a simple detail, yet capable of telling a timeless story.

Among the Folds of the Salento Landscape: The Votive Shrines of a Sacred Tradition

Amid the folds of the Salento landscape—land of ancient traditions and popular faith—votive shrines represent a cultural and spiritual heritage of great value. These small altars, scattered throughout historic town centers and hidden among the olive groves of the countryside, tell ancient stories, legends, and devotional practices that weave together the sacred and the everyday, vernacular architecture and collective imagination.

The Origins and Meaning of Votive Shrines

The Origins and Meaning of Votive Shrines

The term aedicula, in ancient Rome, referred to a small temple or sanctuary, a miniature version of the grand temples dedicated to the gods. In Salento, this tradition evolved into votive shrines: small sacred spaces built outdoors, often embedded into the walls of houses or along country roads, intended to host sacred images of saints, Madonnas, or religious symbols.

Born from the desire to express faith and gratitude—as well as to seek protection and safety—these shrines have played a central role in the spiritual and social life of Salento communities over time.

Town and Country Shrines: Functions and Differences

In the urban fabric of Salento towns, votive shrines are often placed on street corners, small squares, or in front of churches and historic buildings. Here, they become spaces for daily prayer and neighborhood gatherings, guardians of a heartfelt and humble popular religiosity. They also serve to mark important places or devotional routes.

In the countryside, however, the shrines often had a dual purpose: both religious and practical. They served as reference points for farmers and travelers, symbols of protection against storms, illness, or the dangers of working the land. Often located along paths or back roads, they acted as sacred signposts and keepers of legends tied to the land and its rhythms.

The Cunneddhe: Small Architectural Symbols of Identity

In Lower Salento, particularly in the rural areas between Presicce, Acquarica, and Specchia, votive shrines often take the form of what are locally known as cunneddhe. These are small square or rectangular structures with barrel or domed vaults, built entirely of dry stone or plastered, housing sacred images and Marian icons.

The term cunneddha derives from the Latin connetta (small room) and refers to a small covered space, used either for worship or as a resting place for travelers. Often camouflaged among olive trees, these structures act as true rural temples, steeped in spirituality and collective memory.

A striking example can be found in the countryside of Patù, along the road to Marina di San Gregorio: a small shrine made of squared stone blocks houses a now-faded fresco of the Madonna del Passo, venerated as the protector of travelers.

Stories, Legends, and Miracles

Votive shrines are often linked to numerous folk tales and miracles passed down through generations. Stories tell of blessings received, sudden healings, apparitions, and divine protection during disasters. In many communities, these shrines became essential stops during patron saint festivals or processions, nurturing an intimate and collective relationship with the sacred.

In Galatone, for instance, the famous shrine dedicated to the Santissimo Crocifisso della Pietà, carved in stone, gave rise to a widespread devotion that still draws pilgrims from across Salento. In Specchia, the shrine of the Madonna del Rosario on the façade of Palazzo Risolo continues to receive votive offerings during festive days.

Architectural and Artistic Importance

Architectural and Artistic Importance

Though often modest in size, votive shrines are precious examples of vernacular architecture. Characterized by simple yet elegant forms—arches, pediments, and niches—they are adorned with frescoes, paintings, statues, or ceramic tiles. They often reflect the styles and influences of the times and regions in which they were built, representing a continuum between folk art and sacred architecture.

The VIVART Project in Parabita: Reviving Tradition Through Contemporary Art

In Parabita, a small town in the heart of Salento, votive shrines are experiencing a renaissance thanks to the VIVART project—an initiative involving sixteen contemporary Italian and international artists invited to reinterpret these popular sanctuaries through site-specific works.

Some shrines, previously abandoned, and others newly built according to traditional canons, have become vessels for sculptures, installations, and paintings that engage with the place and its history. Artists such as Mimmo Paladino, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Luigi Presicce, and many others have transformed the historic center and rural areas of Parabita into a widespread art trail that merges ancient spirituality with contemporary languages.

Some shrines, previously abandoned, and others newly built according to traditional canons, have become vessels for sculptures, installations, and paintings that engage with the place and its history. Artists such as Mimmo Paladino, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Luigi Presicce, and many others have transformed the historic center and rural areas of Parabita into a widespread art trail that merges ancient spirituality with contemporary languages.

Mayor Stefano Prete emphasizes how VIVART represents a bridge between past and future, capable of reactivating public spaces, stimulating shared experiences, and bringing value to the town’s hidden heritage, turning it into a true “City of the Contemporary.”

Conclusion

The votive shrines of Salento are much more than simple small altars: they are keepers of memory, symbols of cultural and architectural identity, and living spaces of faith and connection. Through initiatives like VIVART, this precious heritage continues to evolve, renewed and enriched by its encounter with contemporary art—ensuring the survival of a tradition that speaks to the heart of the Salento community and to all who visit this land.

The Secret Architecture of the Sea: White Coral, Its Legend, and the Leukos Museum

In the Deep Heart of the Ionian Sea: The Mystery of White Coral

Where the waters of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas embrace, in the silent blue depths off Santa Maria di Leuca, lies a world known to few: a secret realm of white corals, submerged canyons, and petrified forests. Here, hundreds of meters below sea level, there is no sunlight and no human sound—only the slow dance of life patiently building its most fragile and perfect architectures.

What lies hidden in the cracks of the seabed is one of the most astonishing ecosystems in the Mediterranean: white coral bioconstructions (Lophelia pertusa, Madrepora oculata), branching calcareous formations resembling tiny fossil trees that grow in the deepest darkness. Unlike tropical corals, these thrive in cold, still waters between 400 and 1,100 meters deep, feeding on plankton carried by bottom currents.

A Recent Discovery, an Ancient Legacy

A Recent Discovery, an Ancient Legacy

Their presence off the coast of Leuca was only confirmed in the 21st century thanks to exploratory missions led by CoNISMa through the APLABES project, which used advanced sonar and underwater robots. Yet local fishermen had long suspected something: for generations, they avoided certain areas of the deep sea where nets would snag in “an invisible forest.” They called it "the stone forest," believing that ancient spirits or sacred marine creatures lived there.

The images returned by ROVs (Remote Operated Vehicles) revealed an extraordinary landscape: three-dimensional structures up to 2 meters tall, resembling natural cathedrals that provide shelter for rare fish, blind crustaceans, and branching sponges. A delicate balance now threatened by activities such as bottom trawling, ocean acidification, and global warming.

Coral in Salentine Mythology

As often happens with what humans cannot see, legends flourish around white coral. One of the most evocative tells of corals as the solidified tears of a mermaid who fell in love with a fisherman and was punished by the gods. Off Punta Meliso, on calm days, some say you can still hear her song.

Another story, whispered through the alleys of the old town, speaks of a submerged alabaster city swallowed by a divine storm, its domes and towers now covered in white coral—not ruins, but living witnesses of a forgotten world.

Leukos White Coral Museum: Where the Sea Becomes Knowledge

Leukos White Coral Museum: Where the Sea Becomes Knowledge

For those who cannot descend into the abyss but want to experience its wonder, there is a place that evokes it with power and precision: the Civic Museum of White Coral Leukos, just steps from the promontory where Leuca’s lighthouse stands.

Born from the passion of a local collector and developed with the help of biologists and science communicators, the museum is the only one in Italy entirely dedicated to white coral. It's not just a collection of specimens—it's a narrative, sensory, and scientific experience that guides visitors through rare exhibits, microscopes, stories, multimedia panels, and visual enchantments.

Guided Tours: A Journey Through Science, Wonder, and Storytelling

Each guided tour is a short journey led by marine biology experts and passionate educators. The path, accessible to all ages, weaves together scientific knowledge with historical anecdotes, biological curiosities, and local legends. Visitors discover how coral colonies form, what "deep bioconstruction" means, and which species rely on them for survival.

Interactive labs are available for children, while adult visitors will find insights on current topics such as climate change, microplastics, and marine conservation.

A Room, A Story

The museum unfolds across themed spaces:

-

The White Coral Hall, the core of the exhibit, with real specimens from the Ionian Sea

-

The Shell Gallery, featuring surprising shapes and colors from around the world

-

A section on sponges, madrepores, and marine fossils

-

Artifacts collected during scientific expeditions, in collaboration with universities and marine institutes

Why Visit the Leukos Museum

-

It is the only one of its kind in Italy

-

It stems from authentic scientific and cultural passion

-

It offers an accessible and engaging experience for families, schools, and travelers

-

It connects myth, nature, and science in one cohesive journey

-

It is set in one of the most fascinating landscapes of Salento

An Extension of the Sea onto the Land

An Extension of the Sea onto the Land

Visiting Leukos means diving without getting wet, sensing the salt in the air and the sounds of the deep, being carried away by a story that began millions of years ago and continues today through environmental awareness and wonder.

It’s not just a museum—it’s a bridge between worlds.

An Invitation to Discover the Invisible

The white coral of Leuca is a hidden treasure few know about. The Leukos Museum brings it to the surface to reveal its beauty and fragility. It’s an invitation to see the sea with new eyes—more conscious, more curious, more human.

Wheat Architecture in Salento

In the heart of the Mediterranean, where the sun kisses the land and the wind carves its contours, Salento tells its story through wheat. An age-old grain, symbol of life, abundance and spirituality, wheat is an integral part of Salento’s history and identity—not just as food, but as a cultural matrix that has shaped landscapes, architecture, rituals and legends. This deep interweaving of man, nature and architecture gave rise to a rural civilization rich in meaning, now more than ever worth rediscovering.

As early as Messapian and Roman times, Salento was known for the fertility of its fields. The red earth plains, nourished by a mild climate and seasonal rains, were ideal for growing durum wheat. The grain, processed with orally transmitted techniques and harvested with sickles, was the foundation of both the diet and the rural economy.

As early as Messapian and Roman times, Salento was known for the fertility of its fields. The red earth plains, nourished by a mild climate and seasonal rains, were ideal for growing durum wheat. The grain, processed with orally transmitted techniques and harvested with sickles, was the foundation of both the diet and the rural economy.

In the Middle Ages, Benedictine and Cistercian abbeys scattered across the Salento territory helped spread advanced agricultural techniques, organizing the first granaries and mills. Wheat thus became not only an agricultural product, but a driver of local development.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the relationship between wheat and territory is its impact on rural architecture. Salento preserves a unique heritage of underground granaries, especially in the southern part, such as those of Presicce, Specchia, or Sternatia. Carved into the bedrock, often near central squares or within rock settlements, these granaries were cool and dry, perfect for storing grain without mold or infestation.

At the same time, the fortified masserie (farmsteads), built between the 16th and 18th centuries, were equipped with grain pits, underground olive mills, wood-fired ovens, and threshing floors—functional architectural elements still visible in many locations.

At the same time, the fortified masserie (farmsteads), built between the 16th and 18th centuries, were equipped with grain pits, underground olive mills, wood-fired ovens, and threshing floors—functional architectural elements still visible in many locations.

Even the iconic dry-stone walls of Salento outlined and divided the wheat fields, playing a vital role in property management and rainwater containment.

The Threshing Floor: Heart of Rural Life

The aia—or “chiazza” in local dialects—was the heart of agricultural life in Salento. This open-air space, usually paved with limestone slabs or hardened earth, was located near masserie, olive presses, or communal rural settlements.

communal rural settlements.

Both functional and symbolic, the aia was used for threshing wheat. The sheaves were spread out in the sun and beaten with sticks, or trampled by animals pulling heavy circular stone rollers. The result was the separation of the grain from the straw, which was then winnowed and collected.

But the aia was not just a place of work: it was also a space of community, of exchange and celebration. Here, communal harvests were carried out, songs were sung, and fertility rites performed. In some areas, it even became a stage for dances like the pizzica, especially during end-of-harvest festivals—turning toil into festivity.

Many historic aie are still visible and well-preserved. Some have been restored and repurposed, like the one at Masseria Le Stanzie in Supersano, which maintains its original paving, or those in the countryside of Alezio, Nardò, and Giuggianello, often used in summer for cultural events and tastings.

The aia remains a silent witness to a time when every agricultural act was also a communal rite, rooted in the land and in time.

Salento still holds traces of windmills, watermills, and underground mills once used for wheat processing:

Salento still holds traces of windmills, watermills, and underground mills once used for wheat processing:

- The windmill of Torrepaduli (Ruffano) is one of the few restored and visitable ones.

- In Palmariggi, a 19th-century watermill near Montevergine now stands in ruins but remains a point of interest.

- In Calimera, an underground mill integrated with an olive press is now part of the Grecìa Salentina museum network.

- In Cursi, evidence of stone mills can be found in the underground presses, accessible by appointment.

- In the underground granaries of Presicce, some cavities were used as mills powered by hand or animals.

- In Castiglione d’Otranto, the community mill run by Casa delle Agriculture is a virtuous example of rural regeneration, producing flour from ancient grains in a participatory, sustainable way.

- In the Bay of the Water Mill (Otranto), nestled among cliffs and crystal waters, lie the remains of a rock-carved watermill—a rare testament to the harmony between human ingenuity and the coastal landscape.

These structures testify to the ingenuity of farmers in harnessing natural resources to turn grain into flour.

Peasant Traditions: From Grain Cycle to Bread

Peasant Traditions: From Grain Cycle to BreadThe grain cycle marked both the seasons and social life. Sowing took place in November, accompanied by blessing rituals. The harvest, between June and July, was a moment of both hard work and celebration: men and women rose at dawn, sickles in hand, singing work songs.

The harvested grain was threshed on the aia, then brought to the mill. The resulting flour was used to bake homemade bread, often flavored with dried figs, olives, or wild herbs. Bread baking happened in stone ovens, architectural staples of rural homes.

Wheat Between the Sacred and the Profane

Wheat was also rich in symbolic meaning. It featured in religious rites as a metaphor for resurrection and abundance. During the Feast of Saint Joseph, various Salento villages prepare devotional altars decorated with symbolically shaped bread.

During the Feast of Our Lady of Wheat, still celebrated in some rural communities, farmers parade with sheaves of intricately woven wheat. These sheaves were later hung in barns or kept at home as good-luck charms.

Legends of Salento’s Wheat

Legends of Salento’s WheatA local legend speaks of a subterranean dragon, guardian of the underground granaries, who watched over the harvest at night. Only those with a pure heart could approach without invoking its wrath. In other folk tales, the “zitelle del sole” (sun maidens) taught women how to braid wheat into crowns and amulets.

Another legend from Grecìa Salentina tells of the “kalinichti”, kind spirits that appear in mature wheat fields to those who respect the land and its rhythms.

rhythms.

Past and Future: The Return of Ancient Grains

In recent years, interest in ancient Salento grains has resurged—varieties like Senatore Cappelli, Russello, and Timilia, which are less productive but more flavorful and digestible. Grown with organic rotation methods, these grains enhance the territory and offer hope for sustainable agriculture in Salento.

Artisanal mills and rural bakeries, often housed in courtyard homes and restored masserie, now offer stone-ground wholemeal flours and naturally leavened breads, helping to build a short, identity-based supply chain.

The Bread and Stone Itinerary

The Bread and Stone Itinerary

For those seeking to explore authentic wheat-related sites, here is a thematic route through Salento:

- Presicce-Acquarica – visit the underground granaries, historical courtyard ovens, and traditional aie.

- Spongano – 19th-century public oven and bread-making stories.

- Sternatia – underground press with integrated oven and mill.

- Torrepaduli (Ruffano) – restored windmill.

- Calimera and Cursi – underground mills and museums of rural life.

- Masseria Le Stanzie (Supersano) – working oven, historic aia, and bread-making workshops.

- Castiglione d’Otranto – community mill run by Casa delle Agriculture, a model of solidarity economy and ancient grain revival.

- Bay of the Water Mill (Otranto) – scenic coastal bay with remnants of a rock-carved watermill, illustrating the bond between nature and agricultural ingenuity.

Conclusion: Wheat as a Key to Understanding Salento

Wheat is much more than food in Salento: it is a foundation of both material and intangible culture. It has shaped landscapes, inspired architecture, songs, rites and legends. Exploring Salento’s ovens, mills, granaries, masserie and aie offers an authentic way to connect with a heritage that speaks the language of the land, the sun and memory.

Wonders of Stone and Silence: Italy's Most Beautiful Villages in Salento

Among the secret wonders of Salento lie small, suspended worlds, where stone tells age-old stories and every alley holds a fragment of eternity. These are not simply tourist destinations, but places of the soul: Presicce, Specchia, Otranto, and Maruggio, recognized among the "Most Beautiful Villages in Italy," offer a journey through time, amid Baroque and Byzantine architecture, olive trees whispering in the wind, and living traditions.

International tourists imagine Italy as a place of cultural refinement. Our ancient history, scenic beauty, and artistic treasures are the true wealth of our country. Many of the artistic and cultural sites are found in the smallest and least-known towns: the "Most Beautiful Villages in Italy" Association represents the best that Hidden Italy has to offer the world.

International tourists imagine Italy as a place of cultural refinement. Our ancient history, scenic beauty, and artistic treasures are the true wealth of our country. Many of the artistic and cultural sites are found in the smallest and least-known towns: the "Most Beautiful Villages in Italy" Association represents the best that Hidden Italy has to offer the world.

Founded in 2002, the Association promotes small towns that have preserved their beauty and authenticity. With over 360 selected and certified villages, the Association promotes sustainable economic development combined with the protection of historical, artistic, and environmental heritage.

The "Quality Charter" defines the criteria for membership and the methods for awarding the label, a guarantee of excellence and authenticity. Certified villages become top-rated tourist destinations, helping to promote a "local tourism" that is aware and respectful of local cultures.

villages become top-rated tourist destinations, helping to promote a "local tourism" that is aware and respectful of local cultures.

The Association relies on a robust communications network: an annual guide with 50,000 copies distributed, a website with over 1,500,000 unique visitors annually, and social media with more than 2 million followers. The English version of the guide—"The Most Beautiful Villages of Italy"—is designed to promote "roots tourism" and engage an international audience.

Numerous annual events enliven the villages, including the Romantic Night in the Villages of Italy, the National Village Festival, and the Mediterranean Conference. Since 2019, the Association has been ISO 9001 certified for the promotion of national cultural heritage. It also founded the International Federation "Les plus beaux Villages de la Terre" (The Most Beautiful Villages of the Earth) to share and promote the value of these outstanding villages worldwide.

Presicce: The City of Olive Oil and Hypogea

Presicce, in the heart of lower Salento, is a refined and surprising town, known as the City of Olive Oil and the City of Hypogea. Here, everything revolves around the "yellow gold": extra virgin olive oil.

Presicce, in the heart of lower Salento, is a refined and surprising town, known as the City of Olive Oil and the City of Hypogea. Here, everything revolves around the "yellow gold": extra virgin olive oil.

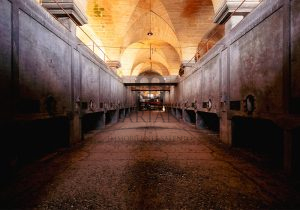

The underground olive oil mills, true underground cathedrals of rural civilization, can be visited in Piazza del Popolo, Vico Sant'Anna, and Via Gramsci. The historic center is an enchanting labyrinth of courtyards and cobbled alleys: don't miss the "li vecchi curti" in the Corciuli and Padreterno districts, with the ancient courtyard houses in Via E. Arditi, Vico Matteotti (1581), Vico Sant'Anna, and Via Anita Garibaldi.

On the Pozzomauro hill stands the small rural church of the Madonna di Loreto, of Basilian origins, next to which lies a Byzantine crypt converted into an olive oil mill.

The surrounding area is dominated by fortified 16th-century farmhouses (La Casarana, Del Feudo, and Tunna) and 18th-century villas, such as Casina degli Angeli (1778) and Casina Celle. A visit to the Museum of Rural Life (Piazza del Popolo) is a must, housing around 300 tools from Salento's rural life.

Presicce captivates with its historic center dotted with Baroque palaces, such as Palazzo Alberti, rich in Neapolitan majolica, and the majestic Palazzo Ducale, with its medieval turret. The churches, including the Mother Church of Sant'Andrea Apostolo, the Church of Carmine, and the Church of the Angels and the Dead, reveal a valuable artistic heritage. The Casa Turrita (or Torre di San Vincenzo) is emblematic, one of the oldest fortifications in the village.

Specchia: The Noble Sentinel of Capo di Leuca

Specchia, nestled among the rolling hills of Capo di Leuca, is one of the most picturesque villages in lower Salento. Its name derives from the ancient

Specchia, nestled among the rolling hills of Capo di Leuca, is one of the most picturesque villages in lower Salento. Its name derives from the ancient "specchie," piles of stones used as observation points. Perched on a hill, Specchia dominates the surrounding landscape with a sober and noble beauty.

"specchie," piles of stones used as observation points. Perched on a hill, Specchia dominates the surrounding landscape with a sober and noble beauty.

Specchia's history is marked by great feudal families, from the Del Balzo to the Gonzaga, and by epic sieges such as that of 1435. Its architecture recounts its past with palaces and castles: above all, Risolo Castle, the Protonobilissimo Risolo Palace, and the Ripa Palace with its frescoed loggia.

The village is a maze of artisan workshops, cobbled alleys, and historic homes: Palazzo Teotini, Palazzo Coluccia, Orlando Pisanelli, and Orlando Pedone are testaments to a glorious past.

Specchia is also a land of artisanal traditions: wrought iron, terracotta, olive wood, and rush are still crafted using ancient techniques.

Nearby, the Terra di Leuca offers natural beauty, sports, and hiking trails. For information, the GAL Capo Santa Maria di Leuca is the right place to organize authentic itineraries.

Otranto: The Pearl of the Orient

Otranto is the gateway to the East, the easternmost point of Italy, steeped in history and culture. Its origins date back centuries: inhabited since the

Otranto is the gateway to the East, the easternmost point of Italy, steeped in history and culture. Its origins date back centuries: inhabited since the Bronze Age, it was an important port for the Messapians, and later a flourishing Roman, Byzantine, and Norman city.

Bronze Age, it was an important port for the Messapians, and later a flourishing Roman, Byzantine, and Norman city.

The Old Town is a maze of narrow streets that wind around the Porta Alfonsina, the Aragonese Castle, and the Norman Cathedral, with its famous Tree of Life mosaic and the crypt housing the relics of the 800 martyrs beheaded by the Turks in 1480.

The small Church of San Pietro, with Byzantine frescoes, and the Palazzo Lopez (now the Diocesan Museum) complete an itinerary that alternates mystical inspiration and artistic beauty.

Otranto is also a vibrant town: the Aragonese walls, artisan shops, seaside bars, and summer events (such as the Medieval Days) make the city lively and welcoming. Its center is a place where history and modernity coexist harmoniously.

Maruggio: Between the Sea, Baroque, and Knights

Maruggio, on the Ionian coast of the province of Taranto, is a village with a unique history: founded between the 9th and 10th centuries, it was ruled by the Templars and then by the Knights of Malta for over five centuries.

Maruggio, on the Ionian coast of the province of Taranto, is a village with a unique history: founded between the 9th and 10th centuries, it was ruled by the Templars and then by the Knights of Malta for over five centuries.

The historic center, known locally as "schiangài," is an enchanting maze of streets, with whitewashed houses, noble palaces, baroque loggias, and flower- filled balconies. Among its iconic sites are the Palazzo dei Commendatori (or Castle of the Knights), the Chiesa Matrice (15th century), the Torre dell'Orologio (Clock Tower) with its war memorial, and the evocative Chiesa di San Giovanni fuori le mura (Church of St. John Outside the Walls), originally intended to accommodate the sick and pilgrims.

filled balconies. Among its iconic sites are the Palazzo dei Commendatori (or Castle of the Knights), the Chiesa Matrice (15th century), the Torre dell'Orologio (Clock Tower) with its war memorial, and the evocative Chiesa di San Giovanni fuori le mura (Church of St. John Outside the Walls), originally intended to accommodate the sick and pilgrims.

Maruggio is also nature: the Campomarino Dunes, up to 12 meters high, are part of the Regional Nature Reserve and protect one of Salento's most beautiful coastlines, with white beaches and crystal-clear sea. The surrounding countryside is dotted with ancient farmhouses and the original Maruggio trulli, dry-stone dwellings made of white stone.

The local forests (Pindini, Sferracavalli, and della Maviglia) offer hiking trails immersed in the Mediterranean scrub, amidst the scents of myrtle, mastic, and juniper.

A Slow Journey Through Culture and Beauty

Presicce, Specchia, Otranto, and Maruggio represent four distinct souls of Salento, yet all united by a profound and authentic charm. These villages are best explored at a leisurely pace, savoring the sun-warmed stone, the freshness of the olive trees, and the embrace of the sea. They are ideal destinations for those seeking timeless beauty, where Italy is still poetic.

Summer 2025 in Salento: art, photography, and architecture between history, experimentation, and new perspectives

Salento is preparing for a summer 2025 dedicated to art in all its forms. Exhibitions, festivals, artist residencies, installations, and photographic journeys unfold across Lecce, Gallipoli, Mesagne, Nardò, and Castrignano dei Greci, creating a dialogue between contemporary creativity and architectural heritage. In this vibrant and ever-changing context, Salento's architecture is not merely a backdrop but a silent and complicit protagonist, capable of giving meaning and depth to every cultural proposal.

Lecce Art Week (20–30 June 2025): the baroque city speaks the language of the contemporary

Lecce Art Week (20–30 June 2025): the baroque city speaks the language of the contemporary

With its fourth edition, Lecce Art Week has confirmed the central role of the Salento capital in the contemporary art scene. Ten days of exhibitions, talks, performances, and widespread installations have transformed historic courtyards, palaces, squares, and deconsecrated churches into true creative hubs.

The Lecce baroque, with its porous and luminous stone, welcomed contemporary experimentation in a play of suggestive contrasts. Sculpted volutes stood side by side with abstract works, multimedia installations, humble materials, and current visual languages, giving life to a fertile friction between memory and vision. The historic architecture amplified the message of the works, providing temporal depth to themes of identity, the body, the landscape, and transformation.

The Time of the Impressionists in Mesagne (27 June 2025 – 6 January 2026)

The Time of the Impressionists in Mesagne (27 June 2025 – 6 January 2026)

At the evocative Norman-Swabian Castle of Mesagne, the exhibition "The Time of the Impressionists, from Monet to Boldini" comes to life—a visual journey through light and color, from late 19th-century Paris to early 20th-century Europe.

The castle, with its stone walls, vaulted halls, and windows overlooking the historic center, proves to be the ideal container for works born in dialogue with natural light. Impressionist painting—vibrant, immediate, and sensitive to atmospheric variations—intertwines here with the light of Salento, creating a parallel between the French and Mediterranean landscapes, between water reflections and whitewashed walls, between ephemeral atmospheres and enduring architecture.

Vittorio Tapparini in Nardò: "Canto Libero" between vision and roots

Vittorio Tapparini in Nardò: "Canto Libero" between vision and roots

In Nardò, a gem of Salento baroque, the historic Chiostro dei Carmelitani hosts the exhibition "Canto Libero" by Vittorio Tapparini, a Salento painter who merges figuration and symbolism in a powerful and intimate expressive research.

The evocative and layered works enter into dialogue with the austere elegance of the convent architecture. The Lecce stone columns, the silence of the cloister, and the sharp shadows that mark the spaces all contribute to making the exhibition a contemplative experience, where art and architecture share the ability to preserve memory and vision.

Gallipoli Photowalk (3 August 2025): capturing the contradictions of beauty

Another innovative proposal for the Salento summer is the Gallipoli Photowalk, a street photography route curated by Fotogrammatica and photographer Paolo Morra, in collaboration with Gabriele Albergo (SalentoDeathValley).

On Sunday, August 3, from afternoon until sunset, a limited group of participants will traverse Gallipoli's historic center, seeking out glimpses, contrasts, and unfiltered truths. Far from postcard imagery, the Photowalk aims to shake the gaze, as Albergo states, revealing a raw, lively, authentic Gallipoli. An experience where architecture and photography interact in real time, in alleys, on stone surfaces, among shadows cast by the sun and textures sculpted by time.

KORA in Castrignano dei Greci: contemporary art and the rebirth of Palazzo de Gualtieriis

KORA in Castrignano dei Greci: contemporary art and the rebirth of Palazzo de Gualtieriis

In the heart of Grecìa Salentina, KORA – Center for Contemporary Art, active since 2021 inside the historic Baronial Palace de Gualtieriis in Castrignano dei Greci, launches a new season rich in visions and languages. On July 4, 2025, the collective exhibition "Selvatica" opens, curated by the IUNO curatorial team, exploring the concept of the wild as a free, untamed space capable of embracing the monstrous and the primordial: works by artists such as Chiara Camoni, Gaia Fugazza, Cynthia Montier, and Marta Roberti transform the palace halls into an inner and emotional landscape, where the stone itself becomes a vessel for contemporary thought. In parallel, Yirong Wu's solo exhibition, "Natura Morta," reflects on the relationship between image, body, and nature, starting from the symbolic figure of the palm tree, a quintessentially Mediterranean plant. A major highlight of the summer is the reopening of the palace courtyard, now a cultural and convivial space through the Korte project: a place where art and daily life meet through music, performances, social gatherings, and creative fusion. On July 4, the "Ogni Altro Suono" festival kicks off the season with a concert by Silvia Tarozzi, while on July 25, KORA hosts the international talk "Wonder Women", featuring Judith Benhamou and other leading voices from the contemporary art and curatorial world.

Conclusion: art and architecture, a natural alliance in the heart of Salento

In all these events, from the Photowalk to international exhibitions, what emerges is the symbiotic relationship between art and architecture. The stones of Salento are not mere scenery—they are living material that absorbs and reflects, welcomes and stimulates the imagination. From Lecce’s baroque vaults to the reborn courtyard of Castrignano, from the silent cloisters of Nardò to the ramparts of the Mesagne castle, contemporary art finds in Salento’s heritage a formidable ally, capable of offering a rare and necessary depth of meaning.

The Green Giants of Salento: When Trees Become Monuments and Architecture

"Trees are poems that the earth writes in the sky." — Kahlil Gibran

The tree represents the bond between earth and sky, between matter and spirit, between nature and beauty. It is a silent, visible poem that speaks to us without words. In Salento, this silent and ancient wealth is hidden, which rises majestically between stone and sky: monumental trees. True arboreal patriarchs, they are not only witnesses of time and history, but become protagonists of a cultural landscape where nature and architecture blend in a harmonious balance. Legends, science, spirituality and a deep bond with the identity of the territory are intertwined in these trees.

Trees as architectural elements: nature incorporated into living

In Salento, monumental trees do not live on the margins of architecture: in many cases they are an integral part of it. In farmhouses, historic gardens, villas and urban spaces, the tree is designed as a living structure, a vegetal column that dialogues with arches, pergolas and courtyards. Examples include the centuries-old olive trees embedded in the dry stone walls of the Strudà and Vernole countryside, or the fig trees or holm oaks that, in the cloisters of former convents or in Italian gardens, mark out the space as columns would in a basilica. In Lecce, in the courtyard of the former Conservatory of Sant’Anna, a 25-meter ficus macrophilla towers among the baroque arches: it is not just a natural element, but an integral part of the architectural scenography.

The Vallonea oak of Tricase: symbol of Salento

Among the most famous monumental trees in Italy is the Vallonea oak of Tricase, planted about 900 years ago and today the guardian of an evocative legend: it is said that in the 12th century it offered shade and shelter to Frederick II and his one hundred knights marching towards the Crusades. 19 meters high, with a crown that covers over 500 square meters, this oak is a witness to the transition from the medieval forestry world to the modern agricultural landscape.

Perhaps imported by the Basilian monks from Dalmatia, the Vallonea oak is today a living natural monument, part of the Otranto–Santa Maria di Leuca Regional Park, and a true emblem of the harmonious interaction between man and nature.

The Araucaria of Taurisano: ornamental exoticism in the Salento villa

In the town of Taurisano, in Villa Lopez, two majestic examples of Araucaria of Queensland, originally from Australia, stand out. Planted in 1880, over 24 meters tall with a base circumference of 4.30 meters, they represent an emblematic case of trees imported to decorate private parks and noble villas, according to a typical taste of the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie. Their presence testifies to the decorative and symbolic function of trees in the historic Salento architecture, in which real acclimatization gardens were created for rare exotic species.

Fitolacca di Veglie: when nature shapes space

In the courtyard of the Masseria La Zanzara in Veglie, now restored but dating back to 1471, grows an enormous Fitolacca dioica, an ornamental tree native to South America. With a crown with a diameter of 17 meters and a base almost 18 meters wide, this tree, planted in 1780, is an integral part of the structure of the masseria. Its central position is strategic: it protects from the sun, offers a meeting point, designs the space. A fascinating example of the intersection between historical architecture and botanical landscape.

The Chilean Palms in Sannicola: plant architecture and colonial memory

At Villa Starace in Sannicola, the entrance avenue is flanked by five Chilean Palms, 15 meters high. Fruits similar to small coconuts, imposing trunks and tropical silhouettes: these trees, imported from the Andes in the 19th century, transform the outdoor space into an exotically inspired garden. They represent the memory of a time when the Salento landscape was contaminated with overseas suggestions, often translated into architectural elements such as greenhouses, pergolas and orangeries.

The Ficus of Lecce: a green column between baroque and spirituality

In the heart of Lecce, near the former Conservatory of Sant’Anna, stands a 250-year-old ficus macrophilla. Planted in the 19th century, it is a rare case of perfect fusion between monumental trees and urban context. The building, designed to host religious women and noblewomen, welcomes this green giant that seems to want to touch the clouds. It is a symbol of naturalistic spirituality, where the tree becomes almost a symbolic elevator upwards, pushing the gaze beyond the roofs and baroque vaults.

The holm oak of Lizzanello and the oak of Taurisano: relics of ancient forests

The holm oak of Lizzanello and the oak of Taurisano: relics of ancient forests

Among the native species, the monumental holm oak, called the "Leccio dei Briganti", of the Pisignano district (Lizzanello), stands out, 23 meters high with a crown that measures 27. Witness of the Mediterranean forests that once covered Salento, it is one of the last giants that survived urbanization and land consumption. Similar is the case of the Virgilian oak of Taurisano, which extends from one side of via XXIV Maggio to the other, incorporating the road and the houses in a green embrace.

Centuries-old olive trees: roots that tell the story of time

No article on the monumental trees of Salento could ignore the centuries-old olive trees, true natural monuments that dot the region with their gnarled trunks. In Borgagne, Vernole, Strudà, Casarano and Alliste there are specimens with evocative names: Lu Matusalemme, Il Re, La Regina, La Testa, La Cascata. Some are more than 3,000 years old and continue to produce olives, from which the DOP extra virgin olive oil “Terra d’Otranto” is obtained. They are living sculptures, witnesses to the resilience of a land that has been able to transform the olive tree into a symbol of identity.

Tree Hugging and the Return to Contact

In Salento, home to ancient and majestic trees, the practice of tree hugging is becoming more and more widespread, an ancient ritual now rediscovered in a therapeutic way. Sitting at the base of an oak, breathing under a holm oak or meditating next to an olive tree is not only an ecological choice but also a gesture of deep connection with nature, which many choose to do in the woods of Tricase, in Pisignano or in the gardens of historic farmhouses.

A heritage to be censused and protected

Since 2015, a national decree has required Italian municipalities to census monumental trees, recognizing the environmental, historical and cultural value of these green giants. Citizens, schools and associations can report notable specimens. A simple gesture, which however protects a fragile and invaluable heritage. In Salento, doing so means preserving not only nature, but the very identity of the territory.

Conclusion: living architecture between heaven and earth

In Salento, monumental trees are not just “nature”, but living architecture, silent columns that support the memory of a territory and dialogue with the constructions of man. They are guardians of beauty, but also of balance: between concrete and green, between past and future. And today more than ever, they remind each of us that the landscape is not something to admire, but something to inhabit with respect.

Hidden Architectures of Salento: Cisterns, Granaries, Legends and Millenary Ingenuity

In the heart of Salento, beneath the apparent aridity of its surface, lies an underground world made of water, rock and collective ingenuity. A civilization of stone and thirst, which for millennia has responded to water scarcity not with resignation, but with intelligence and creativity. In the absence of rivers and lakes, with a deep aquifer and permeable calcareous soils, the Salento populations have been able to transform necessity into virtue, digging wells, cisterns, oil mills and granaries that still today tell stories of survival and collaboration.

A hydraulic civilization born from shortage

Since prehistoric times, the lack of permanent watercourses has pushed the inhabitants of Salento to develop ingenious solutions to collect and conserve rainwater. Rainwater thus became a precious resource, to be intercepted and retained, even in the most inaccessible places. In this context, a geography of widespread settlement has developed, with small inhabited centers each equipped with their own water supply systems.

Since prehistoric times, the lack of permanent watercourses has pushed the inhabitants of Salento to develop ingenious solutions to collect and conserve rainwater. Rainwater thus became a precious resource, to be intercepted and retained, even in the most inaccessible places. In this context, a geography of widespread settlement has developed, with small inhabited centers each equipped with their own water supply systems.

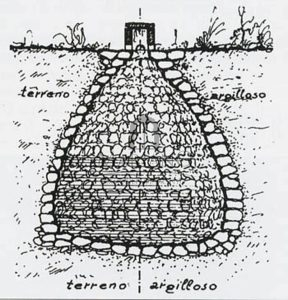

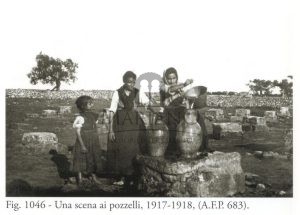

Among the most characteristic solutions are the pozzelle, small underground cisterns shaped like an upturned funnel, dug into natural depressions and lined with dry stones. These artifacts, three to eight meters deep, were sealed with clay and covered with perforated plates, according to a surprisingly effective principle of water filtration and conservation. The pozzelle represent a rare example of community hydraulic architecture, the result of empirical knowledge passed down for generations.

The Pozzelle Parks: Castrignano, Martano, Martignano

Among the places where these structures have found their maximum expression, Castrignano dei Greci stands out, where a natural sinkhole hosts a park with about one hundred pozzelle, some still equipped with stone watering holes for animals and engravings that indicated family membership. Traces of daily use are visible in the marks left by ropes and jugs on the stone mouths.

Among the places where these structures have found their maximum expression, Castrignano dei Greci stands out, where a natural sinkhole hosts a park with about one hundred pozzelle, some still equipped with stone watering holes for animals and engravings that indicated family membership. Traces of daily use are visible in the marks left by ropes and jugs on the stone mouths.

In Martano, according to Giacomo Arditi (1879), there were about one hundred aligned cisterns, each attributed to a different family. Today the area has become an urban square, but the toponym “Pozzelle” and historical sources keep the memory of this collective infrastructure alive.

Still partly active, the Pozzelle of San Pantaleo in Martignano are located on the edge of the town, along the ancient road to Calimera. Of the original 72 wells, 68 remain today. Modern paving has compromised the original water system, but the charm of the place survives also thanks to the legend of San Pantaleo: it is said that the saint, pursued by enemies, found refuge in the interconnected wells, appearing and disappearing magically to disorient the attackers. As a sign of gratitude, he blessed the cisterns, guaranteeing abundant water and protection to the inhabitants.

Zollino: the “Pozzi di Pirro”

One of the best preserved complexes is located in Zollino, in the “Pozzi di Pirro” district. Here there were over 70 wells (today about 40), each with its own name: lipuneddha, scordari, pila, evocative of daily uses and oral traditions. Already in the Land Registry of 1808 these structures were registered as municipal assets, a sign of their central role in the life of the town. Other complexes are located in the Cisterne and Apigliano districts, the latter perhaps dating back to the Messapian or late ancient era, according to the ceramic fragments studied by Silvano Palamà. Zollino has recently started a project to recover and enhance these hidden treasures.

One of the best preserved complexes is located in Zollino, in the “Pozzi di Pirro” district. Here there were over 70 wells (today about 40), each with its own name: lipuneddha, scordari, pila, evocative of daily uses and oral traditions. Already in the Land Registry of 1808 these structures were registered as municipal assets, a sign of their central role in the life of the town. Other complexes are located in the Cisterne and Apigliano districts, the latter perhaps dating back to the Messapian or late ancient era, according to the ceramic fragments studied by Silvano Palamà. Zollino has recently started a project to recover and enhance these hidden treasures.

Monumental wells and cisterns: water as architecture

In Salento there is no shortage of examples of monumental hydraulic architecture. The Cisternale of Vitigliano, for example, is a gigantic underground cistern from the Roman era, over 12 meters long and capable of holding 160 thousand liters of water. Built in cocciopesto, with circular mouths and internal stairs, it is one of the most impressive works of ancient hydraulic engineering in the region.

More widespread, but no less significant, are the rural and urban wells. Some are simple cavities dug by hand, others are real monuments, with arches, columns and engravings that attest to their sacredness and community value. The well was a place of meeting, prayer and social life.

Underground granaries and oil mills: underground economy

Alongside water, food also found refuge underground. The underground granaries, widespread in Presicce, Morciano di Leuca, Specchia and Taurisano, were cool and protected environments, ideal for storing grain away from humidity and parasites. They were not just storage areas, but community spaces governed by shared rules: a true belly of peasant civilization.

Alongside water, food also found refuge underground. The underground granaries, widespread in Presicce, Morciano di Leuca, Specchia and Taurisano, were cool and protected environments, ideal for storing grain away from humidity and parasites. They were not just storage areas, but community spaces governed by shared rules: a true belly of peasant civilization.

Even more spectacular are the underground oil mills, such as those in Presicce, Gallipoli, Sternatia, Vernole and Tuglie. Dug into the rock, they housed the entire production cycle of oil: from crushing to pressing, up to conservation. Men and animals worked there for months, illuminated only by lamps, in a humid and silent environment that smelled of toil and liquid gold.

Itineraries of underground memory

Martignano: discovering the pozzelle and the legend of San Pantaleo

Vitigliano: visit to the majestic Roman “Cisternale”

Presicce and Morciano: exploration of the underground oil mills and granaries

Zollino and Calimera: rural pozzelle still visible

Castro and Santa Cesarea: sea caves and sweet springs that emerge from the sea

Conclusion: a thousand-year-old pact

The underground Salento is not just a hydraulic or agricultural system: it is an invisible geography made of stone, water and collective intelligence. A thousand-year-old pact between man and the environment, in which each cavity tells a story of resistance, community and memory. Where there was no water, they created. Where there was no shade, they dug. Where there was no time, they passed it down.

The most extraordinary landscape is often the one you don’t see.