In the heart of Salento, beneath the apparent aridity of its surface, lies an underground world made of water, rock and collective ingenuity. A civilization of stone and thirst, which for millennia has responded to water scarcity not with resignation, but with intelligence and creativity. In the absence of rivers and lakes, with a deep aquifer and permeable calcareous soils, the Salento populations have been able to transform necessity into virtue, digging wells, cisterns, oil mills and granaries that still today tell stories of survival and collaboration.

A hydraulic civilization born from shortage

Since prehistoric times, the lack of permanent watercourses has pushed the inhabitants of Salento to develop ingenious solutions to collect and conserve rainwater. Rainwater thus became a precious resource, to be intercepted and retained, even in the most inaccessible places. In this context, a geography of widespread settlement has developed, with small inhabited centers each equipped with their own water supply systems.

Since prehistoric times, the lack of permanent watercourses has pushed the inhabitants of Salento to develop ingenious solutions to collect and conserve rainwater. Rainwater thus became a precious resource, to be intercepted and retained, even in the most inaccessible places. In this context, a geography of widespread settlement has developed, with small inhabited centers each equipped with their own water supply systems.

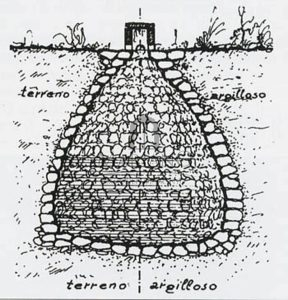

Among the most characteristic solutions are the pozzelle, small underground cisterns shaped like an upturned funnel, dug into natural depressions and lined with dry stones. These artifacts, three to eight meters deep, were sealed with clay and covered with perforated plates, according to a surprisingly effective principle of water filtration and conservation. The pozzelle represent a rare example of community hydraulic architecture, the result of empirical knowledge passed down for generations.

The Pozzelle Parks: Castrignano, Martano, Martignano

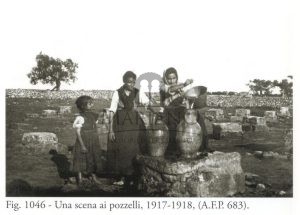

Among the places where these structures have found their maximum expression, Castrignano dei Greci stands out, where a natural sinkhole hosts a park with about one hundred pozzelle, some still equipped with stone watering holes for animals and engravings that indicated family membership. Traces of daily use are visible in the marks left by ropes and jugs on the stone mouths.

Among the places where these structures have found their maximum expression, Castrignano dei Greci stands out, where a natural sinkhole hosts a park with about one hundred pozzelle, some still equipped with stone watering holes for animals and engravings that indicated family membership. Traces of daily use are visible in the marks left by ropes and jugs on the stone mouths.

In Martano, according to Giacomo Arditi (1879), there were about one hundred aligned cisterns, each attributed to a different family. Today the area has become an urban square, but the toponym “Pozzelle” and historical sources keep the memory of this collective infrastructure alive.

Still partly active, the Pozzelle of San Pantaleo in Martignano are located on the edge of the town, along the ancient road to Calimera. Of the original 72 wells, 68 remain today. Modern paving has compromised the original water system, but the charm of the place survives also thanks to the legend of San Pantaleo: it is said that the saint, pursued by enemies, found refuge in the interconnected wells, appearing and disappearing magically to disorient the attackers. As a sign of gratitude, he blessed the cisterns, guaranteeing abundant water and protection to the inhabitants.

Zollino: the “Pozzi di Pirro”

One of the best preserved complexes is located in Zollino, in the “Pozzi di Pirro” district. Here there were over 70 wells (today about 40), each with its own name: lipuneddha, scordari, pila, evocative of daily uses and oral traditions. Already in the Land Registry of 1808 these structures were registered as municipal assets, a sign of their central role in the life of the town. Other complexes are located in the Cisterne and Apigliano districts, the latter perhaps dating back to the Messapian or late ancient era, according to the ceramic fragments studied by Silvano Palamà. Zollino has recently started a project to recover and enhance these hidden treasures.

One of the best preserved complexes is located in Zollino, in the “Pozzi di Pirro” district. Here there were over 70 wells (today about 40), each with its own name: lipuneddha, scordari, pila, evocative of daily uses and oral traditions. Already in the Land Registry of 1808 these structures were registered as municipal assets, a sign of their central role in the life of the town. Other complexes are located in the Cisterne and Apigliano districts, the latter perhaps dating back to the Messapian or late ancient era, according to the ceramic fragments studied by Silvano Palamà. Zollino has recently started a project to recover and enhance these hidden treasures.

Monumental wells and cisterns: water as architecture

In Salento there is no shortage of examples of monumental hydraulic architecture. The Cisternale of Vitigliano, for example, is a gigantic underground cistern from the Roman era, over 12 meters long and capable of holding 160 thousand liters of water. Built in cocciopesto, with circular mouths and internal stairs, it is one of the most impressive works of ancient hydraulic engineering in the region.

More widespread, but no less significant, are the rural and urban wells. Some are simple cavities dug by hand, others are real monuments, with arches, columns and engravings that attest to their sacredness and community value. The well was a place of meeting, prayer and social life.

Underground granaries and oil mills: underground economy

Alongside water, food also found refuge underground. The underground granaries, widespread in Presicce, Morciano di Leuca, Specchia and Taurisano, were cool and protected environments, ideal for storing grain away from humidity and parasites. They were not just storage areas, but community spaces governed by shared rules: a true belly of peasant civilization.

Alongside water, food also found refuge underground. The underground granaries, widespread in Presicce, Morciano di Leuca, Specchia and Taurisano, were cool and protected environments, ideal for storing grain away from humidity and parasites. They were not just storage areas, but community spaces governed by shared rules: a true belly of peasant civilization.

Even more spectacular are the underground oil mills, such as those in Presicce, Gallipoli, Sternatia, Vernole and Tuglie. Dug into the rock, they housed the entire production cycle of oil: from crushing to pressing, up to conservation. Men and animals worked there for months, illuminated only by lamps, in a humid and silent environment that smelled of toil and liquid gold.

Itineraries of underground memory

Martignano: discovering the pozzelle and the legend of San Pantaleo

Vitigliano: visit to the majestic Roman “Cisternale”

Presicce and Morciano: exploration of the underground oil mills and granaries

Zollino and Calimera: rural pozzelle still visible

Castro and Santa Cesarea: sea caves and sweet springs that emerge from the sea

Conclusion: a thousand-year-old pact

The underground Salento is not just a hydraulic or agricultural system: it is an invisible geography made of stone, water and collective intelligence. A thousand-year-old pact between man and the environment, in which each cavity tells a story of resistance, community and memory. Where there was no water, they created. Where there was no shade, they dug. Where there was no time, they passed it down.

The most extraordinary landscape is often the one you don’t see.